Seven lessons I didn't learn from election day

Harris campaigned well! Polling was good! And other null hypotheses.

Our friend Eric Neyman first published this on his blog, Unexpected Values. We liked his deep, data-driven retrospective on how not to update, and thought you would too; enjoy!

I spent most of my election day — 3pm to 11pm Pacific time — trading on Manifold Markets. That went about as well as it could have gone. I doubled the money I was trading with, jumping to 10th place on Manifold’s all-time sweepcash leaderboard. Spending my time trading instead of just nervously watching results come in also spared me emotionally.1

It’s been a week now, and people seem to be in a mood for learning lessons, for grand takeaways. There is, of course, virtue in learning the right lessons. But there is an equal amount of virtue in not learning the wrong lessons. People seem to over-learn lessons from dramatic events. And so this blog post is intended as a kind of push-back: “Here are some lessons that people seem to be learning, and here is why those lessons are wrong.”

The seven most important things I didn’t learn

1. No, Kamala Harris did not run a bad campaign

The most important fact about politics in 2024 is that across the world, it’s a terrible time to be an incumbent. For the first time this year since at least World War II, the incumbent party did worse than it did in the previous election in every election in the developed world. This happened most dramatically in the United Kingdom, where the Labour Party won in a landslide victory, ending 14 years of Conservative rule. But the same thing played out all over the world, in places like India, France, Japan, Austria, South Korea, South Africa, Portugal, Belgium, and Botswana.

Why? The answer is probably inflation: inflation rates were unusually high throughout the world, and voters really don’t like it when prices go up.

The fact that this phenomenon is global shows that we can’t infer much about Kamala Harris’ quality as a candidate, or about her campaign, just from the fact that she lost. Indeed, as the chart shows, she fared unusually well compared to other incumbents (though I wouldn’t read too much into that either2).

Honestly, I don’t think that Kamala Harris was a good candidate, electorally speaking. According to a New York Times poll, 47 percent of voters thought that Harris was too progressive (compare: only 32 percent thought that Trump was too conservative). This is perhaps because she expressed some fairly unpopular progressive views in 2019-2020, including praising the “defund the police” movement and supporting a ban on fracking.

But I think that her 2024 campaign was pretty good. She had a good speech at the Democratic National Convention, did well in the presidential debate, and mostly avoided taking unpopular positions. By most accounts, her ground game in swing states was superior to Trump’s. Plus, Harris was backed by a really impressive Super PAC called Future Forward, which did rigorous ad testing to figure out which political ads were most persuasive to swing voters. Harris’ campaign wasn’t perfect — she should have picked Josh Shapiro as her running mate and gone on Joe Rogan’s show — but I have no major complaints.

Whatever the cause, I think there’s evidence that Harris’ campaign was more effective than Trump in the most important states. Here is a map of state-by-state swings in vote from 2020 to 2024, relative to the national popular vote. In other words, while literally every state swung rightward relative to 2020, I’ve colored red the states that swung rightward more than the nation as a whole, and blue the states that swung less.3

Notice that all seven swing states — Nevada, Arizona, Georgia, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin — swung right less than the nation. Georgia and North Carolina particularly stand out, having swung the least of any states in the Southeast. And despite Harris’ massive losses among Hispanic voters (visible on the map in states like California, Texas, Florida, and New York), she did okay in the heavily-Hispanic swing states of Arizona and Nevada. (See this Twitter thread by Dan Rosenheck for a more rigorous county-by-county regression analysis that agrees with this conclusion.4)

The result? It looks like Harris has pretty much erased the bias that massively benefited Trump in the electoral college in 2020. That year, Biden won the popular vote by 4.5%, but came really close to losing the electoral college. He needed to win the national popular vote by 4% (!) to win the electoral college, a historic disadvantage.

In 2024, it looks like Harris would have needed to win the national popular vote by about 0.3% to win the election. In other words, the last election’s bias against Democrats — a bias that was unprecedented in recent history — got almost entirely erased.

This analysis is not definitive, but it looks to me that the Harris campaign did a basically good job under highly unfavorable circumstances.

2. No, polls aren’t useless. They were pretty good, actually.

I’ve actually seen surprisingly few people complain about the polls this time around. But people will inevitably complain about this year’s polls the next time they’re interested in dismissing poll results. So it’s worth stating for the record that the polls this year were pretty good. I’d maybe give them a B grade.

FiveThirtyEight compares 2024 polls to polls from previous presidential elections, finding that polls had low error and medium bias. Below, “statistical error” refers to the average absolute value of how much the polling average differed from the final result, across relatively close states. Meanwhile, “statistical bias” looks at whether polls were persistently wrong in the same direction.

National polls were similarly biased. It looks like Trump will win the popular vote by about 1.5%, whereas the polling average had Harris winning the popular vote by 1%. That’s a 2.5% bias, which is in line with the historical average:

In 2016 and 2020, we saw a massive polling bias in the Midwest; this year, polls had a modest bias. We only saw a large polling bias on Florida and Iowa, neither or which were swing states.

Why were the polls so biased in 2016 and 2020? For 2016, I think we have a reasonably good explanation: most polls did not weight respondents by education level. This ended up biasing polls because low-education voters swung massively against Democrats, and also were much less likely to respond to polls.

I think it’s less clear what happened in 2020. The best explanation I’ve heard is that the polling bias was a one-off miss caused by COVID: Democrats were much more likely to stay home, and thus much more likely to respond to polls. I don’t find this explanation fully satisfying, because I would think that weighting by party registration would have mostly eliminated this source of bias.

Some people went into the 2024 election fearing that pollsters had not adequately corrected for the sources of bias that had plagued them in 2016 and 2020. I was ambivalent on this point. On the one hand, I think we didn’t end up getting a great explanation for what caused polls to be biased in 2020. On the other hand, pollsters have pretty strong incentives to produce accurate numbers. I hope we end up with a good explanation of this year’s (more modest) polling bias; so far, I haven’t seen one.

Should we expect polls to once again be biased against Republicans in 2028? I don’t know. The polls did not exhibit a bias in the last two midterm elections, but they exhibited a persistent bias in the last three presidential elections. One could posit a few theories:

[The default hypothesis] Every year has idiosyncratic reasons for polling bias. It just so happened that polls were biased against Trump in all of the last three elections: the coin happened to land heads all three times. (After all, if you flip a coin three times, there’s a 25% chance that it will land the same way every time!) Under this theory, we shouldn’t expect a bias in 2028.

[The efficient polling hypothesis] Polls have a reputational incentive to be accurate. Although they were unsuccessful at adjusting their methodologies to get rid of their Democratic bias in 2020 and 2024, in 2028 they will finally succeed in doing so. Under this theory, we shouldn’t expect a bias in 2028.

[The Trump hypothesis] There is a Trump-specific factor that biases polls against him. The most likely reason for this is that some of Trump’s voters (a) only turn out to vote for Trump and (b) are really hard to reach, in a way that isn’t easily fixed by weighting poll respondents differently. Under this theory, we shouldn’t expect a bias in 2028, since Trump isn’t running again.

[The low-propensity voter hypothesis] Some voters only turn out every four years, to vote for president. While a decade ago, a majority of these voters were Democrats, now a majority are Republicans. (This hypothesis is similar to the previous one, except that it doesn’t posit a Trump-specific phenomenon.) Under this theory, to the extent that polls have trouble picking up on those voters (because they’re unlikely to respond to polls), maybe we should expect the bias to continue.

I think these hypotheses are about equally likely. So, should we expect a bias favoring Democrats in 2028? My tentative answer: probably not, but maybe.

There’s one caveat I’d like to make, which concerns Selzer & Co.’s Iowa poll. Ann Selzer is a highly regarded — see this glowing profile from FiveThirtyEight — whose polls have been accurate again and again. But this year, her final poll showed Harris up 3 in Iowa; meanwhile, Trump won by 13 points: a huge miss.

So, what happened? Most likely, the error was a result of non-response bias: more Democrats responded to her poll than Republicans. I couldn’t the poll methodology online, but Selzer is famous for taking a “hands-off” approach to polling, doing minimal weighting. According to Elliott Morris at FiveThirtyEight, Selzer “only weights by age and sex“, basically meaning that she re-weights respondents to ensure a correct number of men vs. women and young vs. middle-aged vs. old respondents, but doesn’t do any other weighting.

This means that if Iowa has equal number of registered Democrats and registered Republicans, but Democrats are twice as likely to pick up the phone as Republicans (after controlling for age and sex), then her polls will show that twice as many Democrats as Republicans will show up to vote.5 By contrast, most pollsters weight respondents by party registration or recalled vote to try to get an unbiased sample of registered voters.

As far as I can tell, this sort of “hands-off” methodology hasn’t been tenable since 2016 and won’t be tenable going forward. My guess is that luck was a major factor in the accuracy of Selzer’s 2016 and 2020 polls. I probably won’t place too much stock on Selzer & Co. polls in future years, though I’m open to being persuaded otherwise.

3. No, Theo the French Whale did not have edge

Theo the French Whale, also known as Fredi9999, was one of the more fun characters of the 2024 presidential election.

Theo the French Whale is actually a human. But in gambling-speak, a whale is a gambler who wagers a really large amount of money. And that kind of whale, Theo was.

About a month before the election, the prediction market site Polymarket started becoming more and more confident that Donald Trump would win the election. While Polymarket had previously been in relatively close agreement with forecast models like Nate Silver’s, Trump’s odds on Polymarket started going up, eventually reaching as high as 66%. Meanwhile, most forecasters thought the race was a tossup.

Traders noticed that the price increase was driven mostly by a single trader with the username Fredi9999, who was buying tens of millions of dollars of Trump shares. A different trader named Domer did some snooping and figured out that Fredi9999 was a Frenchman. The two briefly chatted before Fredi9999 got mad at Domer for disagreeing with him. You can read Domer’s account of it all here.

In all, Theo wagered close to $100 million on Trump winning the election. People posited many theories about Theo’s motivations, but the most straightforward theory always seemed likeliest to me: Theo was betting on Trump because he thought that Trump was likely to win the election.

After the election, a Wall Street Journal report (paywalled; see here for some quotes) revealed Theo’s reasoning: Theo believed that polls were yet again biased against Trump, so he commissioned his own private polling that used a nonstandard methodology called the “neighbor method”.

The idea of the neighbor method is that, instead of asking people who they support, you ask them who their neighbors support. This is supposed to reduce the bias that results from Trump supporters being disproportionately unwilling to tell pollsters that they’re voting for Trump (so-called “shy Trump voters”). According to the WSJ article, Theo’s “neighbor method” polls “showed Harris’s support was several percentage points lower when respondents were asked who their neighbors would vote for, compared with the result that came from directly asking which candidate they supported.”

Many people saw the WSJ report as a vindication of prediction markets. Prediction market proponents argue that we should expect prediction markets to be more accurate than other forecasting methods, because holders of private information are incentivized to reveal that information by betting on the markets. And in this case, Theo even did his own novel research, in order to acquire private information, so that he could reveal that information through his bets! A dream come true for prediction market enthusiasts.

Except, as far as I can tell, the neighbor method is total nonsense. This is for a few reasons.

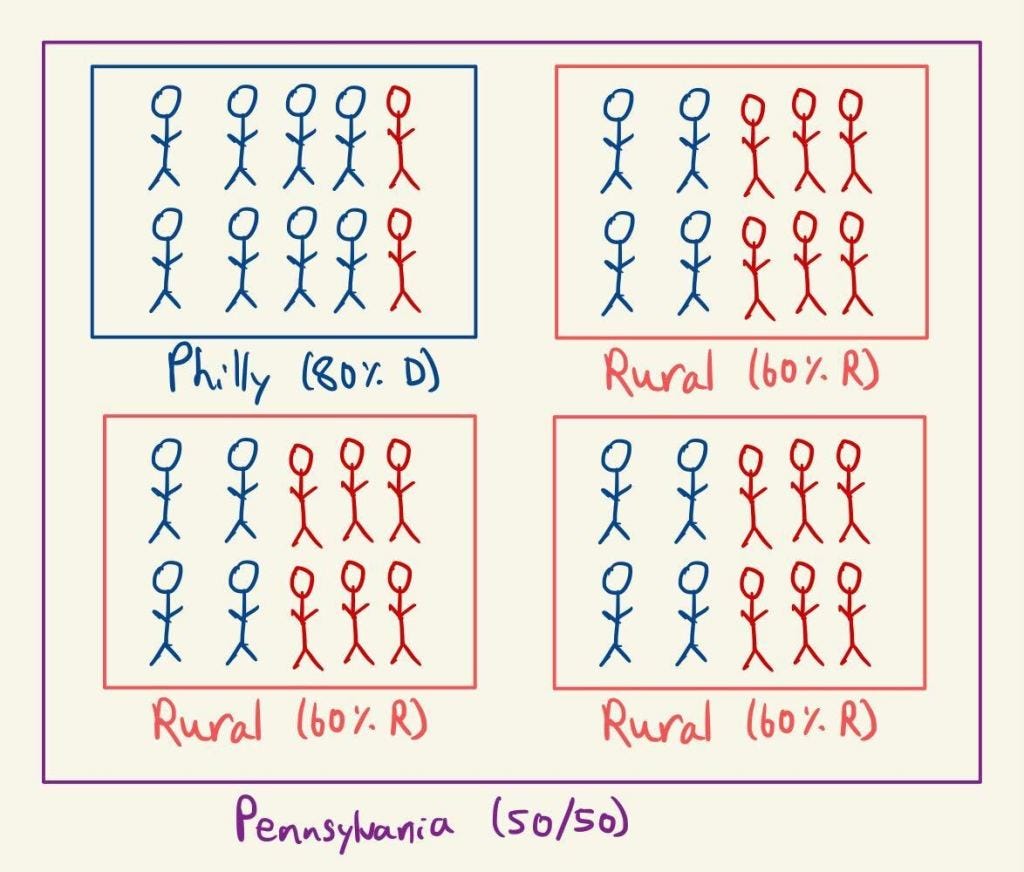

The first reason has to do with the geographic distribution of Democrats and Republicans. Cities are very heavily Democratic, while rural areas are only moderately Republican. As a simple model, imagine that Pennsylvania is split 50/50 between Harris voters and Trump voters, and that in particular:

25% of voters live in Philadelphia, which supports Harris 80-20.

75% of voters live in rural areas, which support Trump 60-40.

If you ask people who they’re voting for, 50% will say they’re voting for Harris. But if you ask them who most of their neighbors are voting for, only 25% will say Harris and 75% will say Trump! It’s no wonder that Theo’s neighbor polls found “more support” for Trump.

(This is just an illustrative example. The actual distribution of voters isn’t as dramatic, but the point still stands: while Trump won 51% of the two-party vote, 55% of Pennsylvanians live in counties won by Trump. This lines up with the shift of “several percentage points” in Theo’s polls!)

The second reason that I don’t trust the neighbor method is that people just… aren’t good at knowing who a majority of their neighbors are voting for. In many cases it’s obvious (if over 70% of your neighbors support one candidate or the other, you’ll probably know). But if it’s 55-45, you probably don’t know which direction it’s 55-45 in.

On the other hand, I could have given you a really good idea of what percentage of voters in every neighborhood will vote for Trump: I’d look at the New York Times’ Extremely Detailed Map of the 2020 Election and maybe make a minor adjustment based on polling. My guess would be within 5% of the right answer most of the time.

So… the neighbor method is supposed to elicit voters’ fuzzy impressions of whether most of their neighbors are voting for Trump, when I could easily out-predict almost all of them? That doesn’t sound like a good methodology.

And the final reason is that the neighbor method’s track record is… short and bad. I’m aware of one serious, publicly available attempt at the neighbor method: in 2022, NPR’s Planet Money asked Marist College (which does polling for NPR) to poll voters on the following question:

Think of all the people in your life, your friends, your family, your coworkers. Who are they going to vote for?

While the main polling question (“Who will you vote for?”) found a 3-point advantage for Republicans (spot on!), the “friends and family” question found a whopping 16-point advantage (which was way off).

(Also, how are you even supposed to answer that question?? “Well, Aunt Sally is voting for the Democrats, while Uncle Greg is voting for the Republicans. Meanwhile, my best friend Joe is planning to vote for the Democrat in the House but the Republican in the Senate. My coworkers seem to be split 50/50 though I don’t talk to them about politics much…”)

So, barring further evidence, I will continue to be dismissive of the neighbor method. Theo did a lot of work, but it was bad work, and he got lucky.

4. No, we didn’t learn which campaign strategies worked

The Kamala Harris campaign is getting a lot of flak for spending millions on swing-state concerts by celebrities lake Katy Perry and Lady Gaga. Had Harris won, the media would probably be praising her youth-savvy strategy.

By contrast, previously-skeptical media coverage of Elon Musk’s efforts to turn out voters for Trump in swing states are increasingly viewed as effective, just because Trump won.

Were the concerts a good use of money? I don’t know. Did Musk’s $200 million get spend wisely? I also don’t know. In both cases, my guess is: probably not. But the fact that Trump won and Harris lost provides very little evidence, just because there are so many factors at play in determining who wins or loses an election.

5. No, Donald Trump isn’t a good candidate

Trump has now gone two-for-three in presidential elections. This year was just the second time that a Republican won the popular vote in the last nine presidential elections (the other being George Bush in 2004). It’s tempting to conclude that Trump is an above-replacement Republican, when it comes to electability. I think that would be the wrong conclusion.

In my opinion, Trump mostly got lucky in the two general elections that he won. In 2016, he barely beat Hillary Clinton, who was deeply unpopular at the time of the election.

And in 2024, he was running against a quasi-incumbent during an unprecedentedly bad time to be an incumbent.

I’m actually not sure that Trump is unusually bad for a Republican. For example, hypothetical Harris vs. Vance polls showed Harris doing about 9 points better against Vance than against Trump. On the other hand, during this year’s Republican primary, most polls showed Haley doing better than Trump against Biden (see e.g. this New York Times poll). Overall, I’d guess that Trump is about average for a Republican in terms of electability.

6. No, spending money on political campaigns isn’t useless

I’ve seen a few people jump to this sort of conclusion based on the fact that Harris significantly outraised Trump and still lost.

But again, the relevant question is how much she would have lost by if she hadn’t outraised Trump. My guess is that she would have lost by more, particularly in the swing states (where most of her ad spending went, and where she overperformed — see above).

Natural experiments show that campaign spending helps win votes. I think that while donating to the Harris campaign is only moderately effective, some efforts such as Swap Your Vote were able to get Harris additional swing state votes at a cost of about $200/vote. As an altruistic intervention, I think this is pretty good, given that the outcome of the presidential election affects how trillions of dollars get spent. (See here for some more of my thoughts about this.)

For my part, I didn’t donate to Harris, but I donated a substantial amount to my favorite state legislative candidate, in what looked to be a really close race. He ended up losing by about 10%, but I think my decision to donate was well-informed, and I would do it again.

7. No, my opinion of the American people didn’t change

I expected 50% of voters to vote for Harris and 48.5% to vote for Trump. Instead, 48.5% voted for Harris and 50% voted for Trump. So I guess 1.5% of Americans have worse judgment than I expected. Those 1.5% were incredibly important for the outcome of the election and for the future of the country, but they are only 1.5% of the population. So perhaps this section’s title is misleading: I very slightly lowered my esteem of the American people as a result of election day.

Put otherwise, I think it was totally reasonable to lower your esteem of the American people in light of the fact that Donald Trump continued to be politically competitive in spite of his role in the January 6th insurrection. That he won this election is an indictment of Americans’ judgment; but if he had just barely lost the election, that would have also been an indictment of the Americans’ judgment.6 I’m simply making the narrow point that we didn’t learn much from election day; almost everything we learned, we learned in 2015-2017 and 2021.

One thing I did learn

Just for fun, I wanted to highlight the most interesting thing I did learn from election night:

Foreign-born Americans shifted toward Trump

Dan Rosenheck points out a really strong relationship between the percentage of a county’s population that was foreign born and how much the county shifted toward Trump. Indeed, the r-squared is 0.51, meaning that foreign-born percentage explains 51% (!) of the variance in how much different counties shifted toward Trump. Every 6% increase in foreign-born population was associated with a 1% increase in swing toward Trump.

(This data is arguably consistent with the theory that foreign-born Americans didn’t swing toward Trump, but rather than native-born Americans who live in immigrant communities swung toward Trump. However, I find this explanation a little less likely, because of some other evidence we have, such as swings toward Trump among Hispanic voters, who are disproportionately foreign-born.7)

I haven’t checked, but I suspect that this is reversion to pre-Trump voting patterns. Maybe otherwise-conservative immigrants voted against Trump in 2016 and 2020, but decided to vote for Trump in this election. If someone wanted to check, I’d be interested in seeing the results!

This was a guest post by Eric Neyman, whose views do not represent Manifold’s. Eric is an AI alignment researcher at the Alignment Research Center in Berkeley, California. His interests include math, computer science, linguistics, geography, philosophy, elections, and public policy.

I was in a room with six or so of my friends. We were all rooting for Harris, but the chatter was all about what trades we should be making. Is the market overreacting to Trump’s crushing victory in Florida? Why is “Trump wins the popular vote” stubbornly staying below 30%? Wisconsin seems bluer than Pennsylvania — should we be buying Trump shares in Pennsylvania and selling them in Wisconsin? Going into election day, I expected that my day would be ruined if Trump won, that I would give up on trading and go cry in a corner. Instead, the opposite happened: the exhilaration of trading — the constant decision-making — displaced most of the grief that I would have felt that day. I think it’s really bad that Trump won, and that the world will be a much worse place because of it. But just on an emotional level, things turned out okay for me.

For one thing, the U.S. economy has generally fared better than most other economies in the developed world. For another, Joe Biden wasn’t running for re-election, which may have dulled the anti-incumbent effect. For a third, the U.S. is unusually polarized, so one should expect smaller swings from election to election. Also, the sample of countries in the chart just isn’t that large.

These numbers are subject to change, mostly because California has so far only counted about two-thirds of its votes.

Rosenheck found that including a variable for “is the county in a swing state?” significantly improves the regression: being in a swing state is associated with a higher vote share for Harris. However, it’s possible that this effect is entirely due to an idiosyncratic pro-Trump effect in a few states like New York, New Jersey, and Florida, which happen to not be swing states.

This is assuming that the Democratic respondents and Republican respondents are equally likely to end up voting. Selzer’s poll is a “likely voter” poll, meaning that she weights respondents by how likely they are to vote.

To be clear, I don’t think that Americans are uniquely bad in this regard. We’ve seen far-right parties surge in Europe, too.

Once we have precinct-level data, this hypothesis could be tested by comparing very heavily foreign-born precincts with surrounding ones. If precincts with tons of immigrants swung more toward Trump than surrounding ones, it would be evidence for my explanation. If they swung less, that would be evidence that native-born Americans in immigrant communities are partly responsible for the swing.

I don’t think we can definitively say “not picking Shapiro for VP was a mistake” because there’s decent contemporary reporting that he actually turned her down for the position. He may have seen the writing on the wall.

Harris isn’t very smart and she ran a terrible campaign and:

After the election the Democratic Party (my party) must rethink many of its policies as it ponders its future.

To be entrusted with power again Democrats must start listening to the concerns of the working class for a change. As a lifelong moderate Democrat I share their disdain for many of the insane positions advocated by my party.

Democrat politicians defy biology by believing that men can actually become women and belong in women’s sports, rest rooms, locker rooms and prisons and that children should be mutilated in pursuit of the impossible.

They believe borders should be open to millions of illegals which undermines workers’ wages and the affordability of housing when we can’t house our own citizens.

They discriminate against whites, Asians and men in a vain effort to counter past discrimination against others and undermine our economy by abandoning merit selection of students and employees.

Democratic mayors allow homelessness to destroy our beautiful cities because they won't say no to destructive behavior. No you can’t camp in this city. No you can’t shit in our streets. No you can’t shoot up and leave your used needles everywhere. Many of our prosecutors will not take action against shoplifting unless a $1000 of goods are stolen leading to gangs destroying retail stores. They release criminals without bond to rob and murder again.

The average voter knows this is happening and outright reject our party. Enough.

XXX