Manifold vs. 538 vs. Everyone Else: Comparing 2024 Election Forecasts

The election’s still basically tied. But who’s winning? (A politics piece by Jacob “Conflux” Cohen)

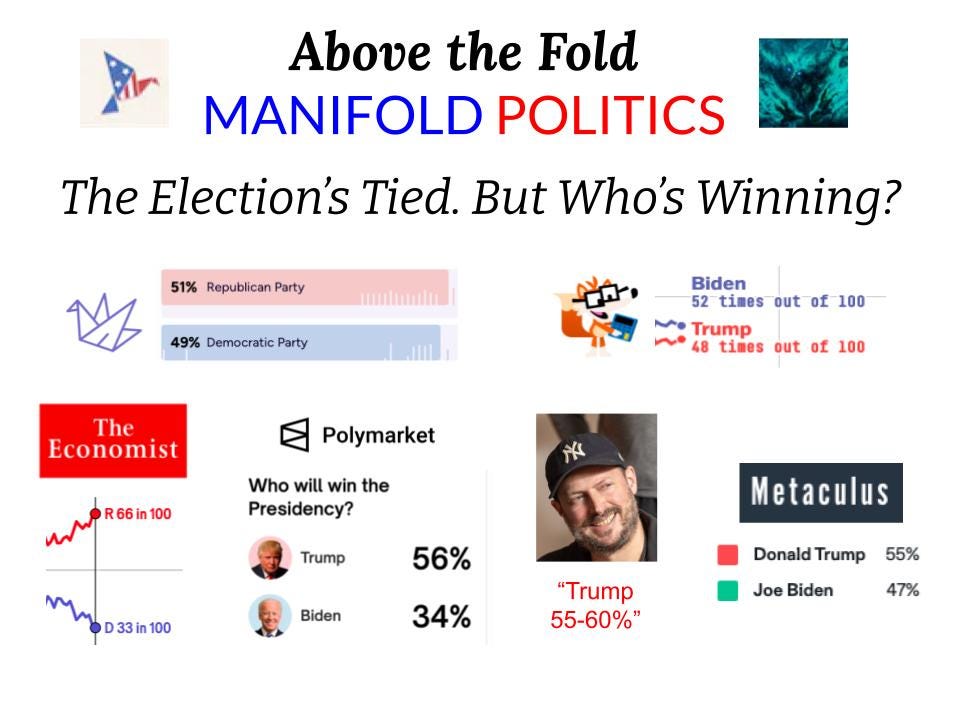

When Nate Silver said at Manifest that Trump had a 55-60% chance to defeat Biden, I did what anyone would do. I opened Manifold and bet M$4000 on Trump to win, bringing him from 49% to 51%.

But was this a bad bet?

This Tuesday, 538 released their model, and Trump was not in the lead. It showed Biden leading — then with a 53% chance! This discrepancy is less surprising when you realize it’s no longer Nate Silver’s 538; the model was created by G. Elliott Morris, with whom Nate has feuded in the past. Morris previously created a model for The Economist that gave Biden a 97% chance of winning the 2020 election, which certainly seems rather high given the razor-thin margins in tipping point states.

This time around, it seems like Morris’s model may still have a Democratic bias, but it’s also underconfident. It assigns a 33% chance that one of the candidates wins in a landslide, getting 350 or more electoral votes (Manifold has it around 15%), a 21% chance that Biden wins Texas (Manifold gives 10%), and a 26% chance he wins Florida (Manifold gives 15%, though it’s been volatile). However, Manifold users disagree on whether this is underconfidence or simply a Democratic skew based on “the fundamentals.”

To continue the election model week, The Economist itself released a new model on Wednesday, and it’s diverged from Silver’s casual estimate in the other direction: it gave Trump a 66% chance to win; this figure has since drifted upward slightly.

There’s also a model from The Hill, which seems to produce the most reasonable output, giving Trump a 56% chance to win the presidency (plus a 77% chance the Republicans take the Senate and a 62% chance they keep the House). Apparently it’s the result of precisely 14,000,605 simulations.

Besides Manifold, which has remained around 51% since my fateful bet, the other betting markets seem close to The Hill’s value. Polymarket has Trump at 56% — though it only gives Biden 34%, and reserves 4% for Michelle Obama; Trump has been known to link Polymarkets on his Truth Social, which may drive bettors from among his audience. Betfair predicts Trump 54%; Smarkets predicts Trump 55% — as does slow-to-update Metaculus. Meanwhile, PredictIt has a 53% chance. This post shows a few other sites.

If you’re not an election junkie, the executive summary is that it’s still an extremely close election — though reading the tea leaves might imply that Trump has the slightest of edges. (In fact, during the time that I was writing this newsletter, the 538 model has slightly ruined my dramatic narrative by now showing Trump with a 51% chance to win.)

Anyway, it’ll be a long election season, and you shouldn’t stress too much about which candidate seems to be winning at any given moment. Plus, we’ll get better information once Nate Silver releases his model (which he retained the IP rights to after leaving FiveThirtyEight) under a paywall in a few weeks. (And guess who bought an $80 subscription to Silver Bulletin for this reason…that’s right, your trusty newsletter author.)

But we can still learn a lot by delving into the details of the diverging forecasts!

(Note: Probabilities in this article may be slightly out of date since I wrote it over multiple days.)

Hello everyone! Conflux here. Sorry I didn’t get an edition of Above The Fold: Manifold Politics out in time to resolve that market YES, but better late than never, you know…

Since my last edition, Joe Biden and Donald Trump have each easily secured enough delegates to be their parties’ nominees. (Though note that Manifold still gives about a 5% chance that Biden isn’t the nominee, likely due to health risks or unprecedented Ezra Klein-ian convention scenarios.)

Neither president has secured a clean sweep: Trump lost in DC and Vermont, two regions with rather liberal electorates and permissive voting rules, to Nikki Haley. Granted, these were still a big surprise to Manifold, with Trump’s chances at around 90% prior to each. Meanwhile, Biden lost the wacky American Samoa caucus not to Marianne Williamson or Dean Phillips but to this random entrepreneur named Jason Palmer who, seemingly, no one had heard of. The market (with, admittedly, a mere 8 traders) literally resolved “Other,” an option which was trading at 2% before the caucus. So, weird things happen! But none of it mattered; the nominees have been largely foreordained for months, as we’ve been in the midst of the longest general election in recent memory.

And it’s a strange beast. From one perspective, it’s deja vu: the same old candidates everyone knows from the last election (and for decades prior), nominated after historically undramatic primaries. Yet the contours are different: Trump is a convicted felon; Biden’s age is a bigger source of concern for voters. The country is no longer as worried about Covid; many have turned to the economy.

In 2020, Biden consistently led national polls by margins from +6 to +10 — although there was a noticeable polling error, and he only ended up winning the popular vote by around 4 points. But this time, Biden’s been on the back foot, with Trump ahead by 1 according to 538’s average. (Given historical discrepancies between polls now and the final result, it should theoretically be unsurprising to see this translate to anywhere between Trump+7 and Biden+5. Also, third-party candidate Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is often getting around 10%, and these supporters may decide between Trump or Biden at the last minute in an unpredictable way.)

Swing States

Of course, the election is decided by the Electoral College, not by national polls.

Well, the tipping-point state is the state that “tips the election to the winner, allocating states in order of decreasing margin.” (It’s not quite the same idea as the closest state, since the “close” states don’t really matter when one candidate wins by a lot. The tipping-point state is essentially the most relevant state for predicting the outcome.) In 2020 it was Wisconsin, and in 2016 it was Pennsylvania. Those two Midwestern states are both trading high, though Arizona, Nevada, Georgia, and Michigan are also listed as possibilities. (The 538 model, bafflingly, thinks North Carolina, where Trump currently leads polls by 6%, has about a 10% chance to be the tipping-point state, essentially tied for second place after Pennsylvania, and has Wisconsin in eighth at 7%, behind the always-just-out-of-reach-for-Democrats Texas and the no-longer-swing-state Florida.) Manifold is more certain, giving Wisconsin and Pennsylvania a nearly 30% chance each to be the tipping-point state.

In Wisconsin, Biden trails in polls by 0.6%, and in Pennsylvania by 1.5%, which is in line with his national numbers — so it doesn’t seem like his Electoral College disadvantage is too bad. 538 gives only a 12% chance that Trump wins while losing the popular vote (and a 1% chance of the reverse) — though these figures are 29% and 8% on Manifold. Outside the Midwest, Biden’s swing-state numbers seem worse: he’s down by at least 4% in Arizona, Georgia, and Nevada, each of which he won in 2020. Again, it’s possible that things change, but these polls provide an objective indicator of what things look like now.

But why do the forecasts show different results? There’s enough polling that it’s hard to fully chalk up the model differences to different ways of interpreting the polls. The reality is that we’re still early in the election season, and there are five months for things to change. So the differences in the forecasts, I think, are largely attributable to different priors for who we should expect to be favored in this strange unprecedented rematch. Or perhaps I should use the more standard election-modeling term to describe them: fundamentals.

Fun with Fundamentals

Perhaps the most fundamental of fundamentals is the state of the economy: it’s long been observed that a good economy makes voters more inclined to support the party in power.

But how do you measure the economy well? Since there are so many economic indicators to choose from, you run the risk of “overfitting,” or creating a very complicated economic formula that predicts past data extremely well but doesn’t hold up for future data. (This is all a consequence of the fact that there simply haven’t been that many recent elections and it’s unclear how representative, say, the 1948 election would be.) Morris’s 538, along with Silver’s, tend to use a basket of canonical indicators which include both objective measures and consumer sentiment; I’m not quite sure of all the details.

In addition to the economy, another common fundamental is incumbency. Does being the current president give you an advantage in the election?

Barack Obama, George W. Bush, and Bill Clinton were all reelected (though not Trump). Especially in the contemporary era of strong negative polarization and low approval ratings, it’s not clear whether presiding over the nation is positive or negative. It’s also unclear how to deal with the fact that he’s a former president. Should he have some kind of incumbency advantage, too? Different modellers might make different decisions here. (Note that one piece of evidence for the incumbency advantage is congressional races, where most incumbents are reelected … though this advantage has been dropping in recent years. It may be mostly name recognition, which would suggest it’s a moot point in 2020.)

Another fundamental indicator is the president’s approval rating, and Biden’s (around 39%) is extremely low by historical standards. His closest recent comparisons are Jimmy Carter in 1980 and George H. W. Bush in 1992, two presidents who lost reelection in landslides.

Some Facts about the Morris 538 Model

The Morris 538 model on release day thinks that Biden’s median outcome is winning the popular vote by 2.3%, so Trump’s lead in polling right now should not be taken at face value. I think this is a bit sketchy, and I am confused by which potential fundamental is giving Biden that much of a lead.

To learn more about the Morris model, you can listen to the 538 podcast on it, which #1 leaderboard trader Joshua recommends. I also liked it! It also has some insights about the model, such as that if they ran a “now-cast” giving results if the election was held tomorrow, Trump would have about an 80% chance to win. This clearly has some implications for the strategy Democrats should take.

Overall Robustness

As Al Quinn writes in a Manifold comment, “As someone who has built predictive models, I can only guess at how many hidden assumptions and parameters they have under the hood to tweak.” My personal opinion is that Morris’s 538 has made a few sketchy ones. The Economist seems a bit overconfident to me, meanwhile, and The Hill seems reasonable — but I don’t know very much about its methodology. Nate Silver’s FiveThirtyEight had a strong track record of making these decisions well, so I’ll be closely watching its results. Something I’m especially curious about: will it replicate any of the strange results of other models, like showing North Carolina as a top-five likely tipping point state, giving Biden >20% odds in Texas or Florida, showing a >25% chance that a candidate wins in a landslide, or giving Trump >60% odds to win overall?

In the meantime, I think I’m going with the Silver-Hill-Metaculus-Polymarket estimate of 55% for my internal probability. I’ve staked some mana on Trump on Manifold as a result. But whatever your opinion, if you disagree with Manifold, you can make some mana (or Prize Points) by betting!

But What Will Happen to America?

However you slice it, your intuition should still consider the presidential race a tossup, and should be prepared for both the Biden and Trump future. However, Manifold Politics has some nice conditional markets that allow you to see some potential differences in Biden's and Trump’s governance! For example, Trump is much more likely to reduce immigration (81% vs. 51%) and appoint another Supreme Court justice (70% vs. 45%) while Biden is significantly more likely to reschedule marijuana (75% vs. 30%). An executive order or legislation related to AI by 2026 is about equally likely under both presidents, though (Biden 73%, Trump 65%). Though as always, beware correlation and causation!

All these are viewable and bettable on the Manifold Politics dashboard.

And over the long soul-crushing months of campaign that will ensue, I think it’s healthy to have some fun. This actually connects to my favorite part of the Manifest conference: no, it wasn’t live-betting based on Silver’s words in Rat Park. It was the great ideas for events that I got: from Michael Wheatley’s historical-retrodiction live-betting event run to Etirabys’s conversational experiments (where you have to pay a little cube to talk for 20 seconds) and conflict improv to the inspiration from Misha Glouberman and Austin Chen’s event on literally how to run events. Finally, I would like to quickly shout out the one and only Trad Egal Trade Gal, co-runner of the Miss Alignment Pageant, agent behind the LessOnline puzzle hunt, the unerasable Ricki Heicklen. (I’m mostly joking here about a slight omission in one of the great writeups of Manifest — there’s Theo Jaffee, Bentham’s Bulldog, Kalshi, and more! — and Austin Chen suggested I write a blog post that “beatifies Ricki,” which “shouldn’t be that hard” since she did so many cool things, which is so true.) I had an amazing time, and hopefully there’ll be a Manifest 2025!

Speaking of fun, and getting back to politics, a few last nuggets before you go…

Close Calls in California

Rep. Adam Schiff and Steve Garvey will be advancing to the general election for California Senate, as Manifold expected (though it also thought Rep. Katie Porter had a shot). However, it was sure that Schiff would not come in second, assigning this event a probability that rounded to 0%.

In fact, it was extremely close between Schiff and Garvey for that position. Schiff ultimately got 0.1 percentage points above Garvey, so it resolved Garvey, but the market went gone back and forth in dramatic fashion.

Meanwhile, in the state’s 16th district (located in the Bay Area, home to such outstanding citizens as Jacob “Conflux” Cohen), the race for second place between Joe Simitian and Evan Low to face off against San Jose Mayor Sam Liccardo was literally tied. Then there was a final recount, and Low won, but by only five votes!

One Last Market

I’m continuing the tradition of adding a shoutout to a market that hasn’t received many traders on a fun/lighthearted/interesting topic. Today’s pick covers the capricious American Samoa caucus — which, as previously mentioned, voted for the “dark horse” Jason Palmer in 2024, and also happened to be the only victory for Michael Bloomberg (with Tulsi Gabbard in second place) in 2020. (Both victories coincided with large expenditures of ad money, by the way.) Will its winner next time around win absolutely anywhere else? The 4 bettors so far give it coinflip odds.

I’ve personally added an M$1,000 subsidy to the above market to encourage accuracy.

Concluding Thoughts

Thanks for reading to the end of this edition of Above The Fold: Manifold Politics! I know this newsletter wasn’t maximally thorough — there are many methodological rabbit holes that one can go down — but I decided to make a time vs. thoroughness tradeoff; let me know what you thought of that. And we’re still taking suggestions if you have them.

I’ve been Jacob Cohen, known on Manifold as Conflux. I blog at tinyurl.com/confluxblog, make puzzles at puzzlesforprogress.net, and don’t release any new episodes of the Market Manipulation Podcast on your favorite podcast platform. Check out Manifold Politics at manifold.markets/politics, or via its Politics or 2024 Election categories. And if you enjoyed this newsletter, don’t forget to like, share, and/or subscribe to Above the Fold on Substack!

Thanks to top traders Gabrielle and SemioticRivalry, along with others in the Manifold Discord, for great conversations which influenced the ideas in this post. Thanks to Nikki for proofreading!