Experiments with Futarchy

Manifold becomes a battleground for a long-standing debate

What is a futarchy and how do we break it?

It’s not that often that an entirely new system of government is proposed, which is why Robin Hanson’s proposal from the turn of the century for a form of government based around the capability of markets to aggregate information has had some staying power in forecasting circles.

Futarchy, as it’s called, proposes:

Continuing to use democratic processes for determining “what it is” that we want. Think values, moral outcomes, and metrics for determining the welfare or growth of a community.

Using betting markets to allow anyone to bet on conditional probabilities for which candidate/policy/decision would lead to the best outcomes, as determined by step 1.

Following whatever policies these prediction markets view as most likely to result in a favorable outcome.

Now, I’m sure you’re already thinking of about a thousand reasons why this would fail, but Hanson and other proponents of futarchy have defended it against rote concerns like discount rates making long-term forecasts difficult, perverse incentives such as people betting for the policies they like, market manipulation, etc.

And of course, imagine hearing a basic description of another form of government, like the mixed republic. “So… uh… there are two legislative bodies, in one of which the seats are allocated by population, and in the other the seats are allocated two per state, some of these states are fifty times larger than others… and there’s also a unitary executive who has basically no bounds on their power unless they’re impeached by the legislature… and there’s a constitution which is interpreted by a series of judges appointed by the executive…”

As with everything, the devil is in the details and there’s no such thing as free governance. So much of what makes a system of government viable and robust is the body of political theory and jurisprudence underlying it.

Now, futarchy is not going to supplant the republic any time soon, but it might be useful in limited cases. One classic example from Hanson is that it could be used to make decisions on the investiture of CEOs. You could make markets on whether the stock price of a company would go up if the CEO is fired, and given US law on the responsibility of corporate governance, this actually lines up pretty well with their explicit incentives.

But back in June, blogger Dynomight dropped a fairly aggressive critique of futarchy. They had been writing on the topic for a while, echoing previous sentiments on why futarchy might have trouble disentangling causal relationships from probabilistic relationships, but this new post was fairly clear and if true, they argued, constituted a “fundamental flaw”. That’s worse than a normal flaw.

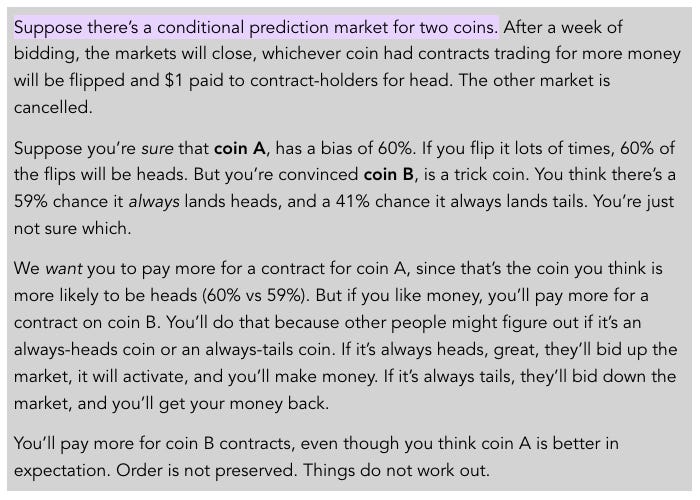

Here’s the thought experiment that illustrates this. You might want to read this carefully:

It sounds esoteric, but replace coin with policy and flip with “observe outcomes” and you basically have the precise, recommended use-case for futarchy.

In any case… someone made the market.

Fundamentally flawed

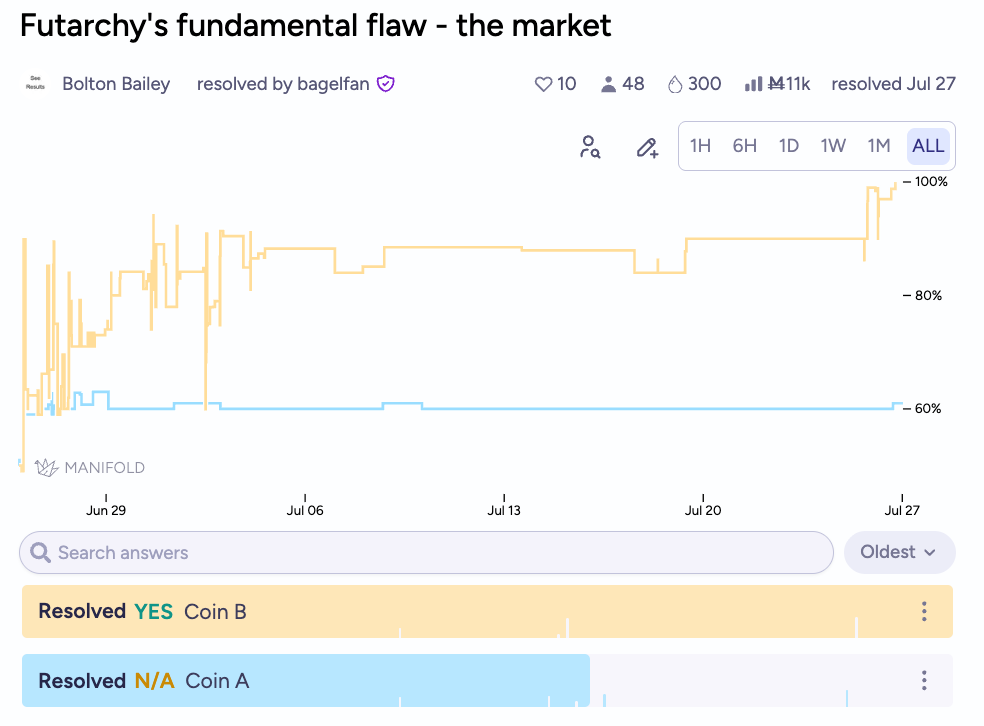

Manifold user Bolton Bailey did precisely this, and as you can see, market behavior fairly rapidly sent Coin B up to 90%, perhaps even more of a clear demonstration than Dynomight would have expected!

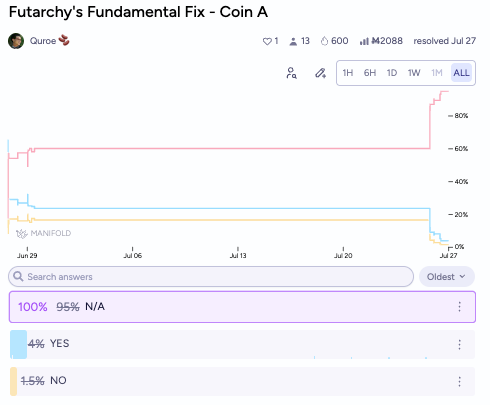

Another user thought that creating derivatives markets for both coins might fix this. It didn’t. Despite the creation of the derivative markets, the main market kept the large discrepancy between the odds for the two coins.

Dynomight then declared victory:

The fact that this is possible is concerning. If this can happen, then futarchy does not work in general. If you want to claim that futarchy works, then you need to spell out exactly what extra assumptions you’re adding to guarantee that this kind of thing won’t happen.

I think it’s a cool market, and it was very astute of Dynomight to predict the market’s dynamics in advance, not something to take for granted.

However, many Manifold users disagreed with this characterization. I thought about the market… then spoke with Isaac King, Manifold’s second-most-prolific market creator, to get his perspective… then I thought about it some more.

Ultimately, I think Dynomight is right in that the edge case they’ve set up is fundamentally flawed and does not do a good job of executing a conditional market with meaningful probabilities. But then I thought about how a similar critique about any other system of government (or really, any tool for governance) might go.

The Republic’s Fundamental Flaw:

Suppose there’s an election to pick which of two parties should run the country. 60% of the population wants Party A to win, and 40% of the population wants Party B to win. I divide everyone in the population up into 10 regions, such that in 6 of the regions, 55% of the population votes for Party B, electing a representative from that party, and in the other 4 regions, 82.5% of the population votes for Party A, electing a representative from that party.

Now, we have 6 representatives from Party B and 4 from Party A, despite a clear majority preferring Party A.

Okay, gerrymandering is of course a real concern with republics, but I don’t think it makes sense to describe it as a fundamental flaw of the system. Perhaps care must be taken to minimize its effects, but it’s one of many, many downsides of that magnitude for a republic.

Thus, I think Dynomight could always retreat to the motte of “care must be taken to avoid designing conditional markets susceptible to this issue,” but I think the bailey is indefensible.

Here are other issues with futarchic systems that one would need to take care to avoid:

They’re only as precise as the discount rate on the capital being placed into the market. If I can earn 4% in a high-yield savings account, why would I correct a conditional market on which candidate is more likely to lead to a war with Venezuela by 2030, or something? Even if that market is priced at 50% and I think it should be priced at 80%, if the two candidates have equal chances of winning (half the time, my bet is N/A’ed), then it’s not worth my time investing there at all!

Conditional markets are only as good as their criteria. I could make a market “Under which president would war with Venezuela be more likely?” and then define “war with Venezuela” as an attack on any ship that left Venezuela, even in international waters. By that definition, we’d already be at war with them, and I might not be evaluating what I wanted to be evaluating.

Robin Hanson swears up and down that market manipulation is not an issue, but I think this is just completely false. A recent study, carried out on Manifold(!) supports my conclusion, as does common sense. Of course, over time, the manipulators will lose money and everyone else will gain money, but there are other ways of making money in society outside of prediction markets and it will take a long time for society to reach some stable equilibrium in this regard.

In particular, Dynomight and Bolton Bailey’s experimental market has a couple of characteristics where I think the analogy to gerrymandering makes sense. Just like with gerrymandering, it requires some artificial manipulation of the system to get to these unfair outcomes. In particular, it requires:

That we have perfect information about the odds of the two coins (ahem, candidates). This is almost never the case in real-world decision-making. We cannot know with absolute certainty that there is a 59% chance of our president invading Venezuela, say.

That one of the options has that information revealed before the arbitration of the market. This would be like one of the candidates committing to swearing a blood-oath to either invade or never invade Venezuela one week before the election, but not saying which they would do until that date.

That the futarchy market is predictably self-resolving. This would be like conditionalizing the election on the result of which candidate would be more likely to invade Venezuela, rather than, say, the average of several markets, or the actions of a council who have pledged to make their decision only from futarchy markets, or any number of other mixed systems.

You can imagine that this thought experiment, which works well for coin flip predictions, might not work so well when the outcome is some complex formula of general welfare outcomes, or something as inscrutable as “stock prices.”

I would say, then, that it makes more sense to describe the “fundamental flaw” of futarchy as being the same as any other system of government. That is that there is no such thing as free lunch in governance. If you attempt to reduce any system of government to some minimalist form where it can be subject to simple and pure experimentation, you’ve essentially broken it irredeemably and it should come as no surprise that it fails to operate as intended.

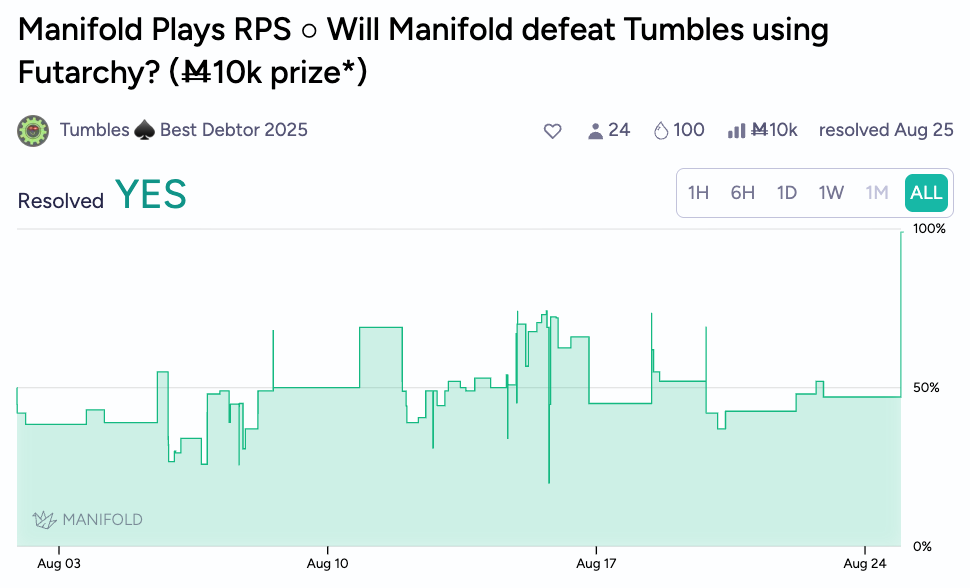

In any case, another experiment was conducted on Manifold to test futarchy shortly after.

And in this one… futarchy won.

Rock paper scissors futarchy

Here were the rules for this experiment:

Tumbles is allowed to bet on these options when each round starts, but is prohibited from betting on this market within 12 hours of the round ending

Round ends and decisions are finalized at 4:20 pm PST

If Tumbles is very late to create a market, resolution will be delayed 24 hours to make sure decision markets are always open for at least 16 hours

Tumbles locks in his move each round before creating the decision markets for that round

Decisions are messaged to @Stralor via discord, an ex-user of Manifold with a good reputation, so that moves can be verified if needed

Decisions are also posted in the comments as an MD5 hash

Each round there are three options, one for each of Rock/Paper/Scissors

At resolution time each round (4:20pm), the option with the highest percentage becomes Manifold’s chosen action

The two options that are not chosen immediately resolve N/A

This chosen option will stay open until the entire set of RPS games is complete, and resolve based on whether Manifold won the best of seven

Chosen option is determined based on what can be determined by looking at the regular interface, not the api

In the case of a tie between two options, RPS rules determine which option is chosen (ROCK beats PAPER, etc)

In the case of a tie between all three options, ROCK becomes the chosen option

Despite the adversarial format, and despite the fact that there was asymmetric information benefiting Tumbles, futarchy still won, in a closely fought match, 4-3.

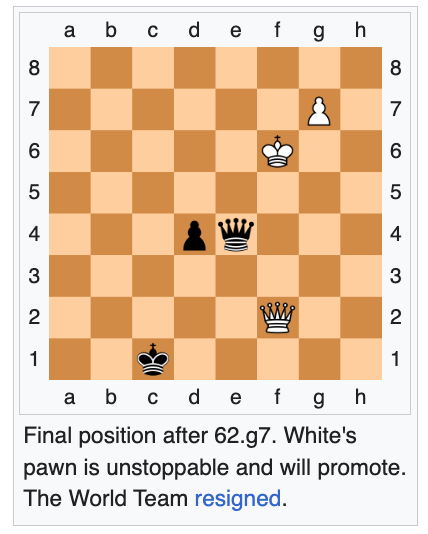

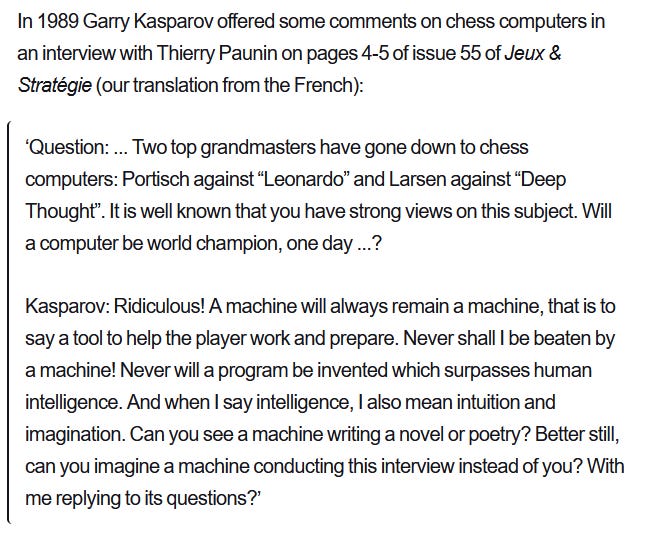

Do I actually think this is a meaningful test of the efficacy of futarchy? On one hand… no. On the other hand, the last time that the world got together to beat a master of strategy games, the great Garry Kasparov, they used a mixed democracy, rather than a futarchy, and lost.

Futarchy 1, democracy 0.

Roundup

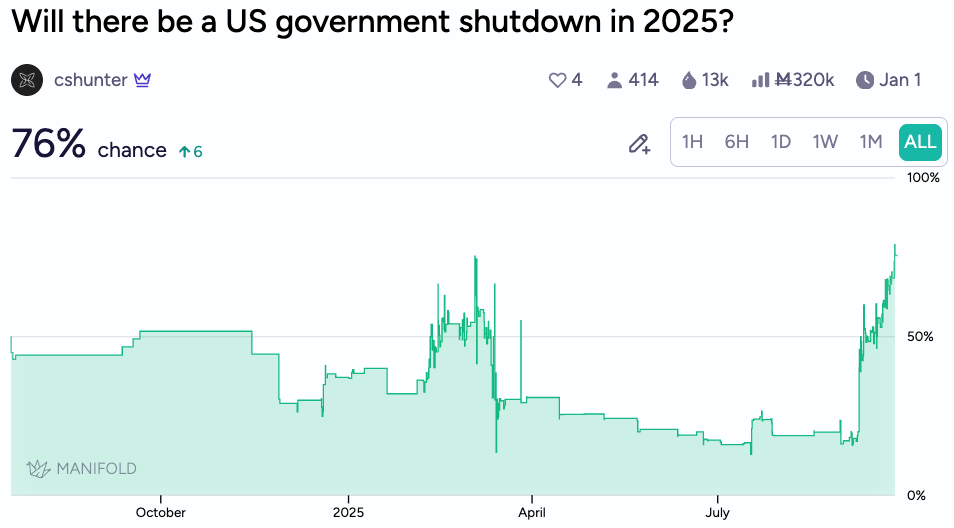

In other news, shutdown odds are up to 76% on the year (yikes)…

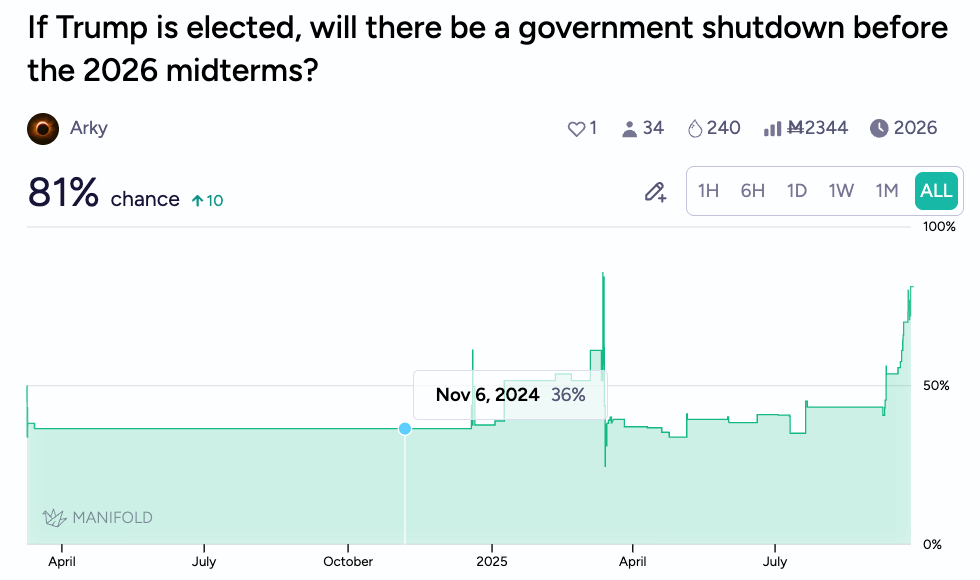

…despite the conditional market pricing this at only 36% back in November. Unfortunately, no one made a similar conditional market for Harris, which would have been nice for comparison.

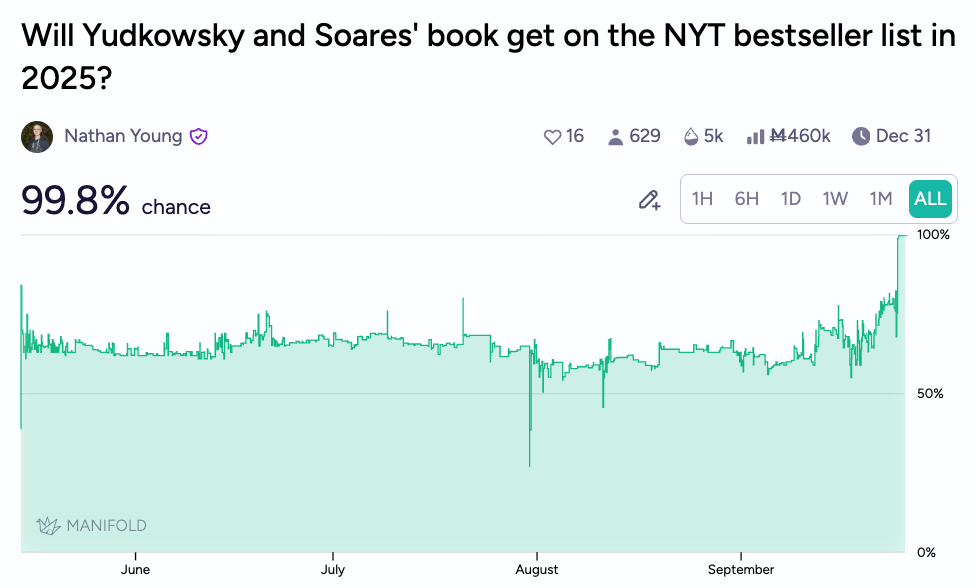

MIRI’s book, “If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies” did indeed get on the NYT bestseller list, slotting in at #7.

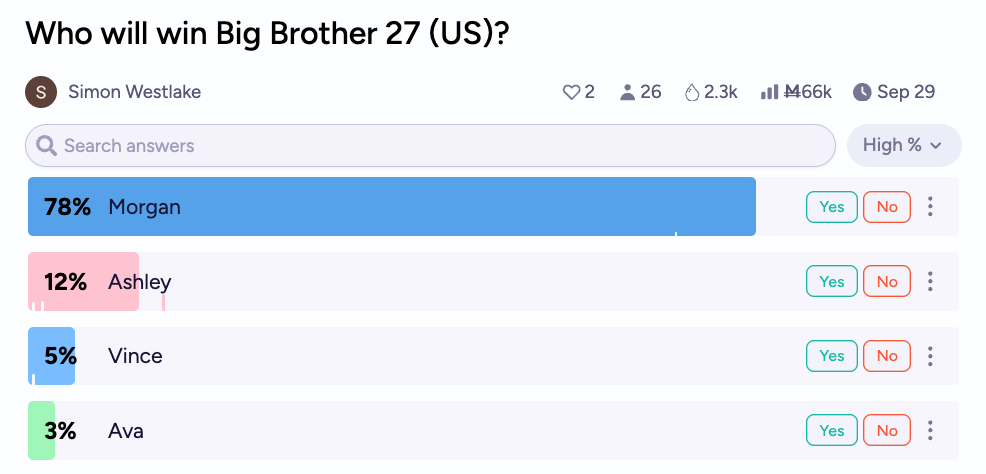

Manifold thinks that (uhh, spoiler warning, perhaps?) Morgan is very likely to win Big Brother 27 ahead of the remaining members of the house.

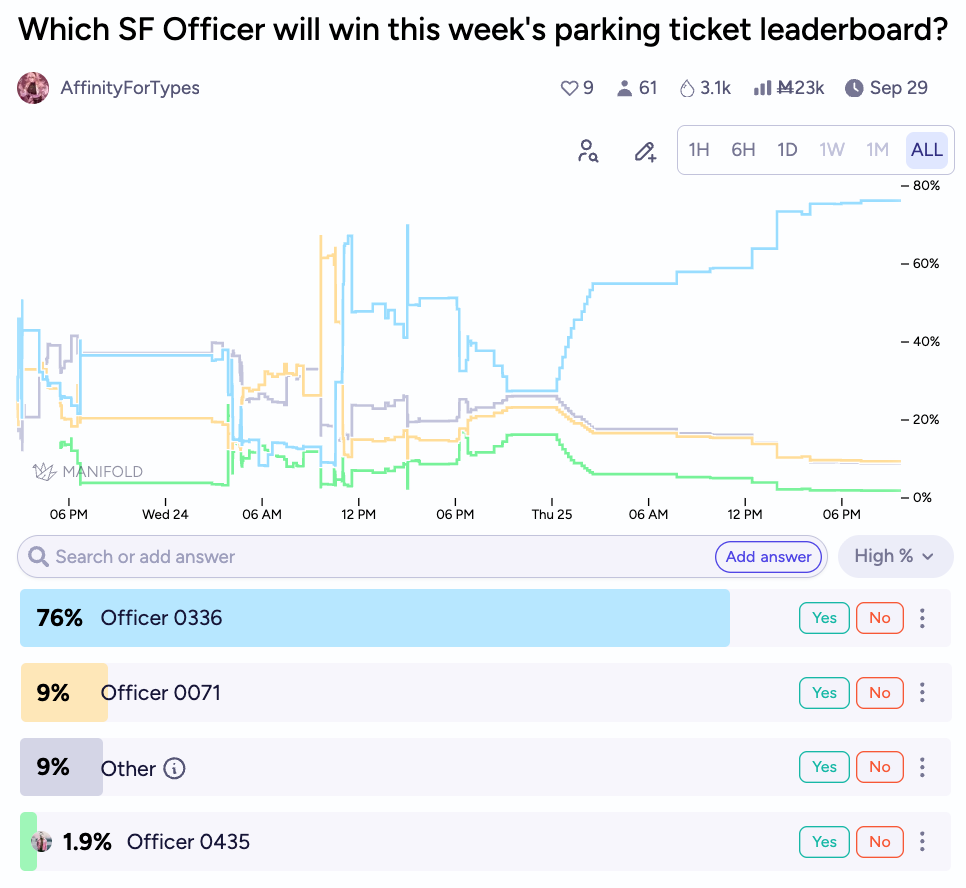

And Officer 0336 (O’three for short) appears to have almost as good odds at winning this week’s parking ticket leaderboard!

Happy Forecasting!

-Above the Fold

P.S. This quote from Kasparov that I found on r/singularity amused me (his takes on AI are only a little better now, 36 years later):

Even though my derivative market “Futarchy's Fundamental Fix” failed to fix the percentages, I think it was a fun attempt to science out a solution. If it didn't work, it didn't work! And now we know!

Good post, you might also be interested in these markets (sorry if you already linked to them!)

https://manifold.markets/Tumbles/futarchys-fundamental-flaw-the-mark-d9LsnOnzhI

https://manifold.markets/Tumbles/futarchys-fundamental-flaw-the-mark-OR85qIqIcN