Carriers and Consequences

The world's largest oil reserves and America's shortest attention span

From Caracas to Crisis

Venezuela wasn’t supposed to be here. In the 1970s, it was Latin America’s success story: the largest proven oil reserves in the world, strong ties with Washington, a capital that looked more like Miami than anywhere else south of the Rio Grande. American oil majors worked alongside PDVSA to develop the country’s heavy crude reserves. The money flowed, Caracas prospered, and nobody thought too hard about what would happen when the oil prices stopped cooperating.

The problem, obviously, was that nobody diversified. When oil prices collapsed in the ‘80s, the whole elaborate structure came apart. Corruption metastasised. By the 1990s, Venezuela was experiencing the kind of economic crisis that destroys faith in institutions and creates market opportunities for radical alternatives.

Hugo Chávez provided that alternative. Elected in 1998 on a platform of socialist transformation and anti-American rhetoric, he nationalised oil assets, purged PDVSA of anyone who disagreed with him, and channelled oil revenue into ambitious social programs. For a while, when crude was trading high in the 2000s, this appeared to work. The fact that it was entirely dependent on sustained high prices and was actively hollowing out the country’s productive capacity became obvious around 2014, when oil crashed and the entire structural basis went with it.

Venezuela’s oil production collapsed from 3.5 million barrels per day to under 500,000 by 2020. Hyperinflation hit 130,000% in 2018. Over seven million Venezuelans fled the country (roughly a quarter of the population), creating the largest refugee crisis in the Western Hemisphere’s modern history. Chávez died in 2013, leaving power to Nicolás Maduro, a former bus driver whose main qualification for the presidency appears to have been unwavering loyalty. Maduro has held power through increasingly authoritarian methods: contested elections, violent crackdowns, and imprisoned opposition leaders. His 2018 and 2024 elections are widely regarded as fraudulent by everyone except the people conducting them.

This is where we are: a country in economic free fall, governed by a regime most of the international community considers illegitimate, sitting on oil reserves that could reshape global energy markets if properly developed, located uncomfortably close to American shores. What could possibly go wrong?

Double-Tap Diplomacy

On September 2, the U.S military struck a boat in the Caribbean. The first strike killed nine people. Two survivors clung to debris. According to the Washington Post, Defence Secretary Pete Hegseth gave an order to “kill everybody.” Admiral Frank Bradley ordered a second strike that killed the survivors.

The Pentagon’s Law of War Manual (with perhaps it’s most competent use-case since the name-change) says, “Persons who have been incapacitated by wounds, sickness, or shipwrecks are in a helpless state, and it would be dishonourable and inhumane to make them the object of attack.” The Geneva Convention prohibits conducting hostilities on the basis that there shall be no survivors.

The White House denied that the second strike occurred. Then on Monday, press secretary Karoline Leavitt confirmed it happened but said Bradley gave the order, and it was “self-defence to protect Americans and vital United States interests.”

Senator Angus King: “If the facts are as alleged, that’s a stone-cold war crime. It’s also murder.”

Since September 21, Strikers have destroyed 22 boats, killing 83 people. Fishermen in Trinidad and Tobago have stopped venturing far from shore. Their livelihoods are collapsing because they fish in waters where summary executions now occur. Venezuelan Defence Minister Vladimir Padrino calls the strikes “an undeclared war.”

Bipartisan congressional investigations have been launched. Republicans are split. Rep. Mike Turner told CBS that if the double-tap occurred as described, it’s “an illegal act.”

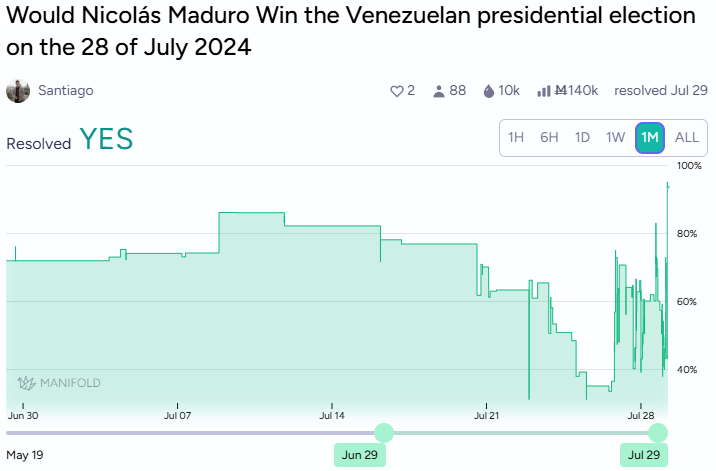

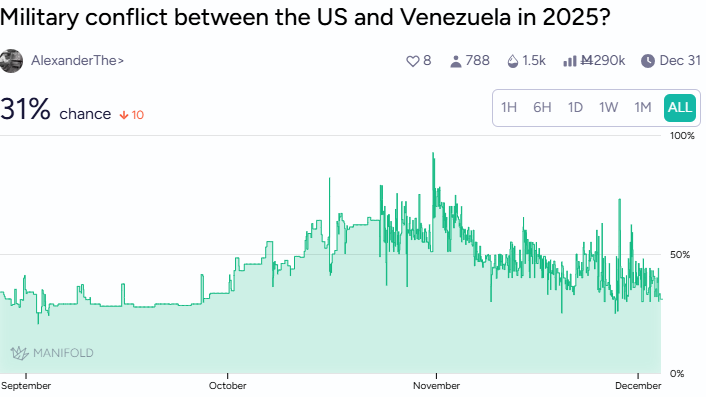

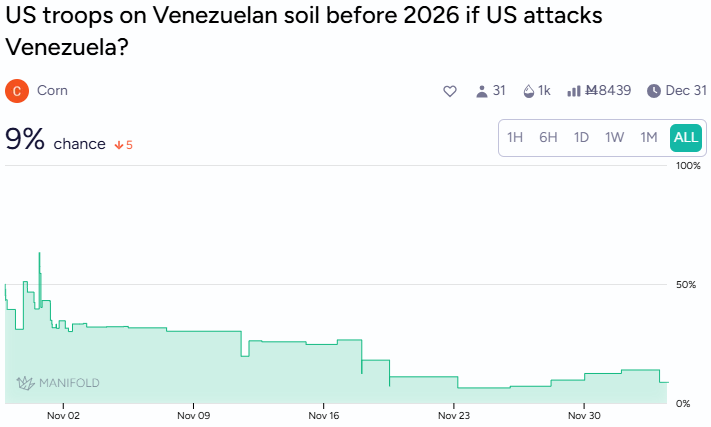

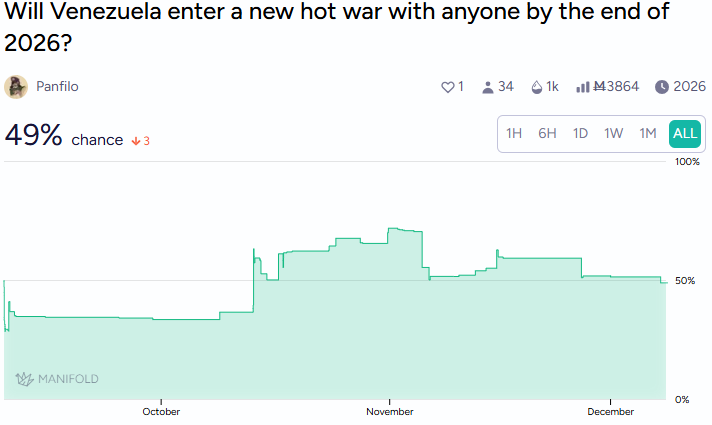

Markets give 31% odds of U.S. military action against Venezuela before year’s end, down from 65% in early November.

Markets also give 9% odds of U.S. troops on Venezuelan soil before 2026 (provided a US military action).

F-35s and Other Anti-Drug Assets

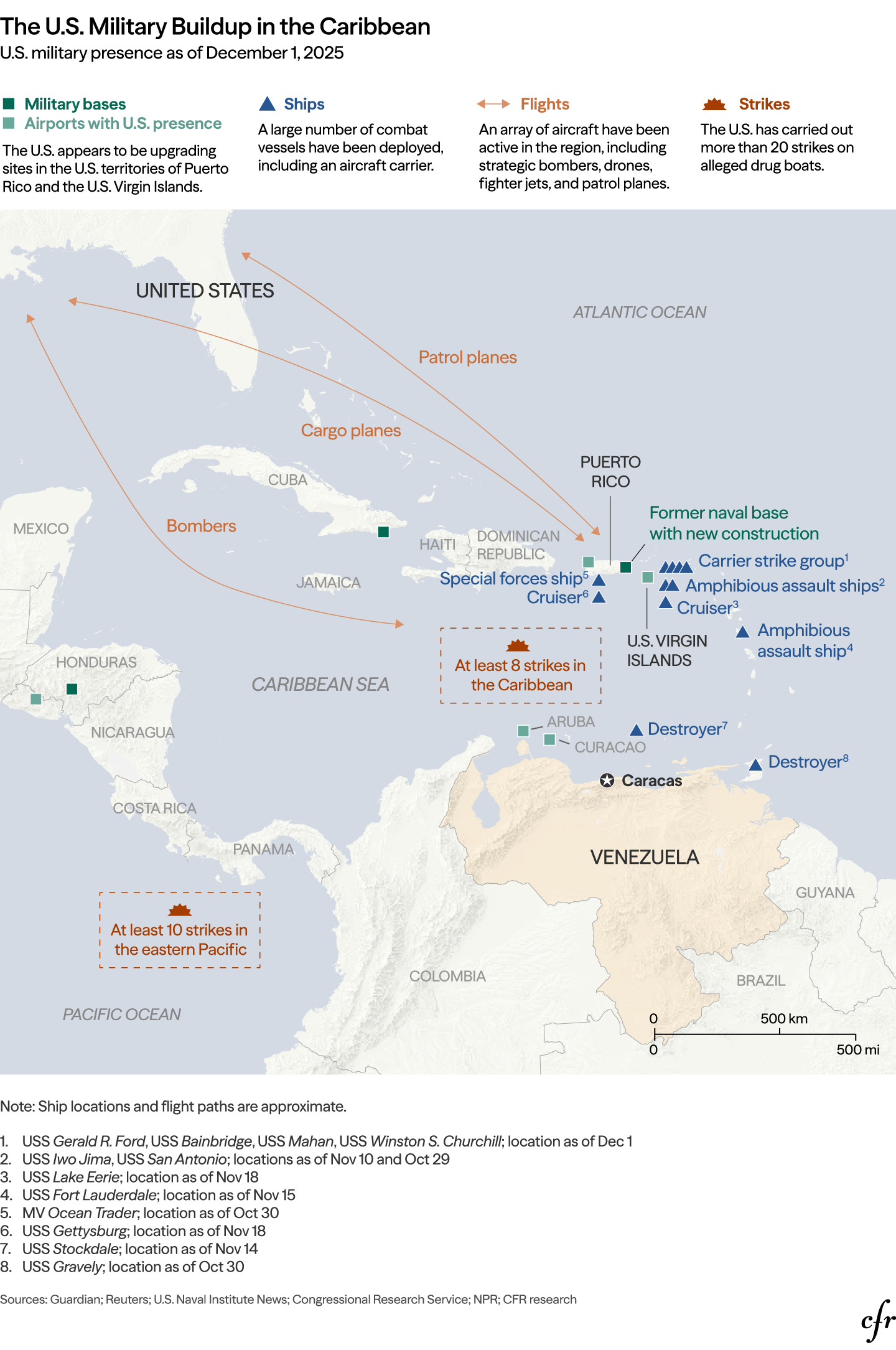

Nine naval vessels: Arleigh Burke destroyers, a Ticonderoga cruiser, a nuclear attack submarine, the USS Iwo Jima with 2,500 Marines. Ten F-35 stealth fighters in Puerto Rico flying nearly around the clock. The USS Gerald R. Ford, the world’s largest aircraft carrier, in the region. Fifteen thousand American troops positioned in the Caribbean.

You don’t need F-35s to intercept drug boats. This is the toolkit for regime change: air superiority, command destruction, special operations.

Military analysts call this a “strategic shot clock.” Carrier groups can’t maintain station indefinitely. Either Trump uses this force or withdraws it or maintains posture indefinitely, which is unsustainable.

Maduro has mobilized the military, deployed 15,000 troops to the Colombian border, called for civilian militia enlistment. Venezuelan F-16s have conducted confrontational flights near U.S. ships. Last week he addressed supporters in full military dress, waving Simón Bolívar’s sword.

Trump, in Trump fashion, declared Venezuelan airspace “closed in its entirety” on Saturday, then told reporters Sunday not to “read anything into” it.

The current deployment is insufficient for full-scale invasion but adequate for surgical strikes. This matches Trump’s preference for air power over ground deployments. Whether it works when governing the aftermath requires more than destroying things is another question.

The Succession Question

The U.S. has recognized Edmundo González Urrutia as Venezuela’s legitimate president. Most independent observers believe he won the 2024 election before Maduro declared victory and forced him into exile.

The opposition’s face is María Corina Machado, who won the Nobel Peace Prize in October 2025 but has been in hiding since July 2024. Barred from running, she backed González while remaining the movement’s ideological leader. She leads Vente Venezuela, favouring PDVSA privatization, free-market reforms, and “foreign intervention on humanitarian grounds.”

Machado has no executive experience. The opposition coalition is fragile, united by opposition to Maduro rather than shared governance vision. Deep divisions exist on economic policy, how to handle Chavista beneficiaries, what to do about military officers complicit in authoritarianism and crime.

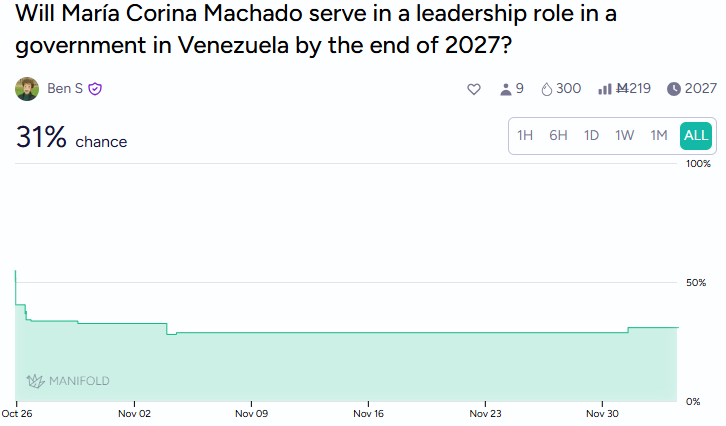

Manifold gives Machado 31% odds of serving in Venezuelan government leadership by 2027.

Last month Barclays organized a private meeting in Washington with Machado to discuss investment opportunities. Widely attended by investment firms and hedge funds. Machado’s team has held informal conversations with the World Bank, IMF, and Inter-American Development Bank.

UBS has circulated memos describing Venezuela as “a land of opportunity” and “a blank slate.”

Regional Enthusiasm (or the lack of)

Colombia, governed by leftist president Gustavo Petro (whom Trump sanctioned), opposes both Maduro’s authoritarianism and Trump’s military threats. Colombian cooperation would be essential for intervention. That cooperation is absent.

Brazil’s Lula opposes foreign military intervention despite condemning Maduro’s fraud. The regional consensus: Maduro is terrible but American military action would be worse (thinking perhaps marked by the rich history of US intervention in Central & South America).

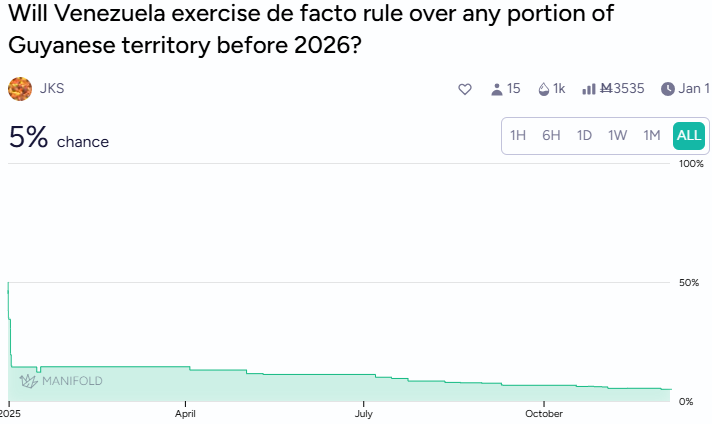

Venezuela claims 70% of Guyanese territory. Markets give 5% odds Venezuela will exercise de facto rule over portions before 2026.

If Maduro invades Guyana while facing U.S. threat, the crisis compounds.

Cuba and Russia prop up Maduro with financial support and weapons. Iran has deepened cooperation on drone technology. China maintains economic ties. Xi Jinping sent Maduro a letter calling the nations “intimate friends, dear brothers” and stating China “resolutely opposes the meddling of external forces.” In a famous clip from September, Maduro waved around the latest Huawei model, “the best phone in the world, and the Americans can’t hack it.”

The US’s Splendid History of Nation-Building

Nobody has explained what happens after Maduro is gone.

The economy has collapsed more thoroughly than Iraq: per capita GDP down 75% since 2013, worse than the Great Depression. Oil production cratered. Infrastructure decayed. Millions of professionals fled. The currency is worthless.

The military is complicit in repression and organized crime. Machado’s free-market vision has limited appeal among Venezuela’s poor, who benefited from Chavista programs (regardless of how economically unsustainable they were). Any post-Maduro government faces dual demands from creditors: Venezuela defaulted on $150 billion, and pressure for unpopular reforms.

Markets give 52% odds of civil war before 2050.

Libya and Iraq demonstrate how state collapse metastasizes. The U.S. would need military presence to prevent chaos, train security forces, mediate between factions. Nation-building, which Trump’s brand rejects and his voters were promised wouldn’t happen.

Pentagon officials have expressed private concern: surgical strikes remove Maduro, government collapses, armed groups fight for control, humanitarian crisis worsens, U.S. faces pressure for ground troops in an unstable situation.

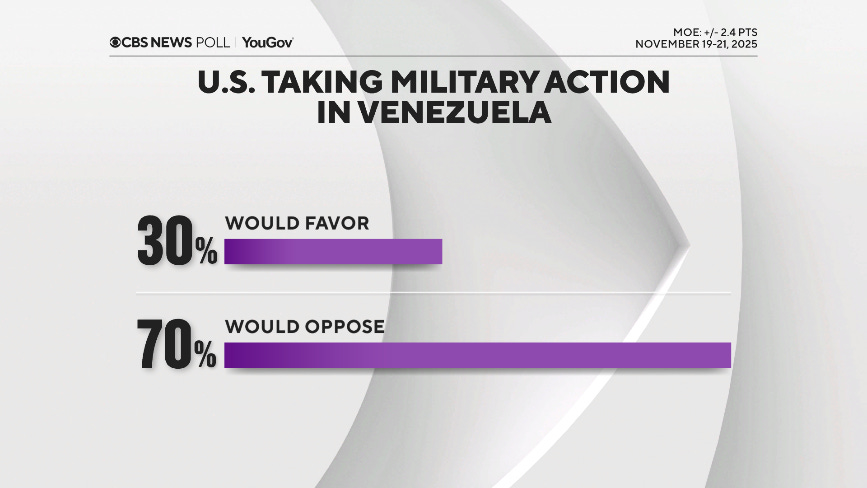

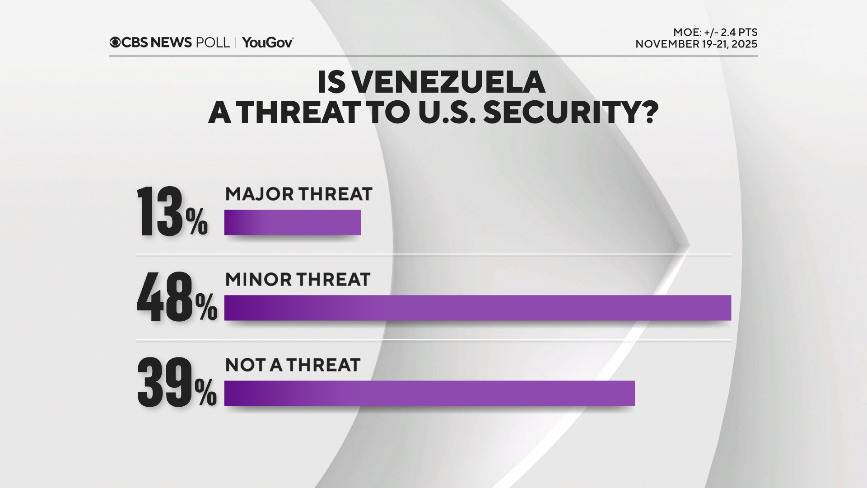

A CBS/YouGov poll shows 70% of Americans oppose military action in Venezuela. Only 13% consider Venezuela a major threat.

Trump’s 70% Problem

Trump’s coalition support for Venezuela is fracturing. MAGA activists support drug trafficking crackdowns but are wary of mission creep. Trump campaigned on ending “stupid foreign wars.”

Trump held an Oval Office meeting Monday with Hegseth, Gen. Dan Caine, Marco Rubio, Susie Wiles, and Stephen Miller to discuss “next steps.” What those steps are remains unclear.

Trump confirmed he spoke with Maduro by phone. “I wouldn’t say it went well or badly. It was a phone call.” He said the U.S. would “start doing those strikes on land, too” and suggested expanding operations: “Anybody doing that and selling it into our country is subject to attack.”

The administration designated the “Cartel de los Soles” as a foreign terrorist organization, providing legal cover to treat this as counterterrorism rather than war requiring congressional authorization. The Cartel de los Soles isn’t actually a cartel, it’s Venezuelan slang for corrupt senior officials.

Trump this week pardoned former Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández, convicted on major drug trafficking charges. The timing struck many as contradictory given the stated rationale for Venezuela operations. Florida Rep. Maria Salazar: “I would have never done that.”

The Shot Clock Runs

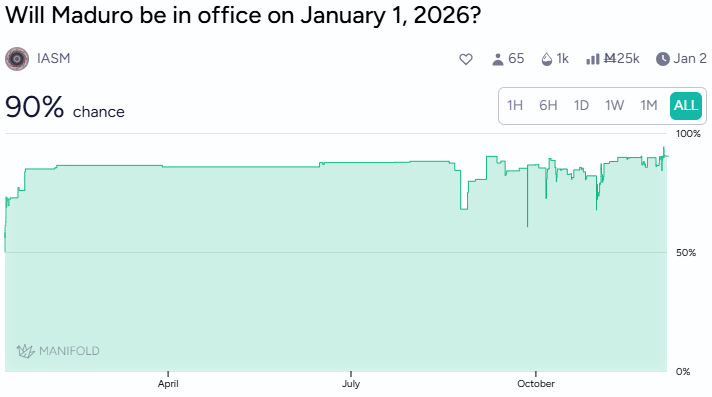

Markets give 90% odds Maduro finishes 2025 as president, suggesting they think the status quo is more likely than dramatic change. This disconnect between Trump’s rhetoric and forecasters’ scepticism reflects Trump’s pattern of threatening action without following through, the obvious costs of intervention (costs which are already providing to be decisive), and perhaps overconfidence that advisors will restrain him.

The markets may be wrong. Trump has demonstrated a willingness to use force when it serves his interests, and domestic political incentives for appearing tough on Venezuela are strong. The regime is genuinely unpopular across the political spectrum; there’s no meaningful Maduro constituency in American politics. If Trump decides that removing Maduro is achievable and politically beneficial, the assembled assets could be used within days.

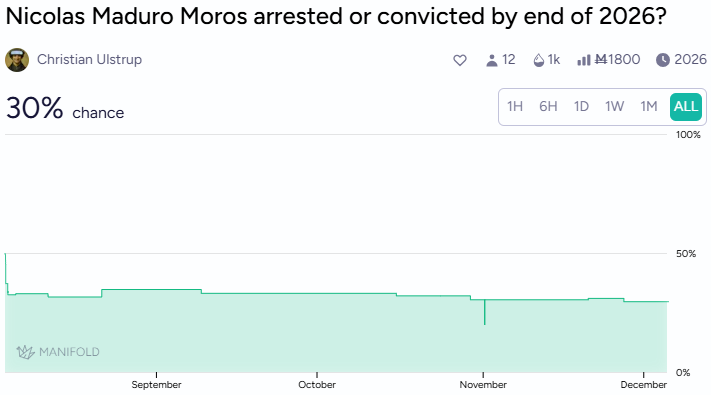

Markets also aren’t against the idea of his arrest or conviction, with traders giving a 30% chance it happens before the end of 2026.

Whatever happens, the Venezuelan people continue paying the highest price for a crisis decades in the making. Seven million in exile, millions more trapped in economic collapse. The current campaign has so far mostly succeeded in killing fishermen, terrorising coastal communities, and creating precedents for extrajudicial killings that will be cited by authoritarian governments worldwide for years to come.

If regime change succeeds, Venezuela faces years of instability and the question of whether American-backed reforms can deliver better than Chavismo did. If it fails, the U.S. faces the humiliation of assembling a massive military force and achieving nothing while strengthening Maduro’s position domestically. Carrier groups and hundred-million-dollar bounties create their own momentum. Whether any incoming action leads anywhere better than the current crisis remains very much an open question.

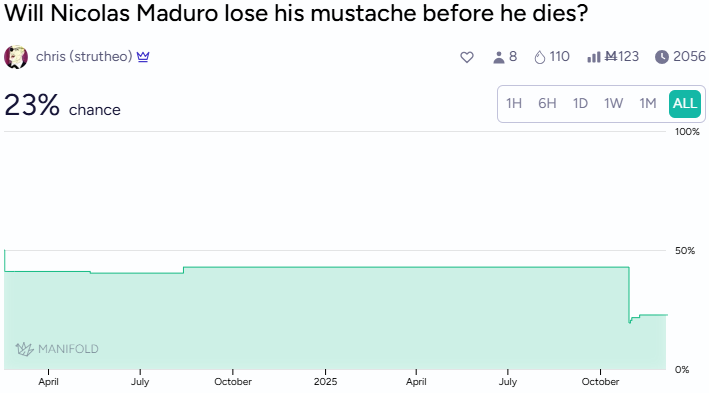

While Venezuela’s political future may be uncertain, Manifold traders are at least intent on tracking Maduro’s facial hair.

Happy Forecasting!

-Above the Fold