Above the Thames

What happens when the centre cannot hold (and isn't trying)

British politics has entered what historians might generously call “a period of transition” and what everyone else recognises as barely controlled chaos. In this piece, we examine Reform’s inevitable rise and what happens when they actually govern, Labour’s three strategic choices, the Greens’ surprising populist transformation under Zack Polanski, Brexit’s refusal to stay settled, and why Scotland keeps asking the same question. Plus: what markets tell us about 2029’s realigning election.

The Reform Trajectory

To understand Reform UK’s rise, you need to understand what they’re actually selling. Reform is selling a simple story: Britain’s problems have obvious causes and obvious solutions, and the only reason we haven’t solved them is because the political class refuses to do what’s necessary.

This is an appealing pitch in a country where living standards have stagnated for over a decade, where NHS waiting lists grow longer, where housing costs have made homeownership a fantasy for an entire generation, and where the promised benefits of Brexit have failed to materialise. The traditional parties offer technocratic solutions and incremental improvements. Reform offers clarity, but the problem is that the clarity they’re offering won’t actually solve any of these problems and might well make them worse.

The irony is profound: Reform (previously the Brexit Party, before that UKIP) was instrumental in delivering Brexit, which was supposed to fix precisely these issues. Brexit passed, yet these problems haven’t gone away. But rather than prompting reflection, this failure has been reframed as evidence that Brexit wasn’t done properly, that the establishment sabotaged it, and that we need to go further.

This is familiar terrain for anyone watching politics across developed democracies. Reform’s ideology slots neatly into a global rightward shift remaking politics from Trump’s America to Meloni’s Italy to Milei’s Argentina. The underlying structure is remarkably consistent: economic anxiety channelled into cultural grievance, declining faith in institutions, and nostalgia for a version of the nation that may never have existed but feels more real than the present.

Nigel Farage understands this dynamic better than anyone in British politics. He has spent two decades moving the Overton window by first making extreme positions speakable, then acceptable, then mainstream. Brexit is the obvious example, but watch how quickly Reform’s positions on immigration, human rights legislation, and international institutions shift from fringe to Conservative Party policy. Farage doesn’t need to replace the Conservatives when he can simply drag them toward his positions (though at this point, replacement seems more efficient).

Reform’s recent local election performance (with 677 council seats won) reflects growing appeal. Reform voters understand the pitch: simple explanations for complex problems, external enemies to blame, and the promise that if we just remove the right people or leave the right institutions, prosperity will naturally follow. They’ve concluded the system isn’t working for them (which is correct), and that Reform offers the most compelling alternative (which is considerably less so).

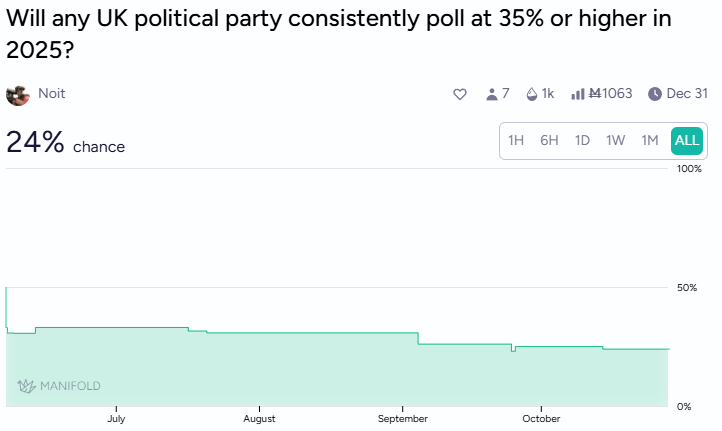

The UK’s first-past-the-post electoral system creates a perverse outcome. When the anti-Reform vote splits across Labour, Conservatives, Liberal Democrats, and Greens, Reform can win a commanding parliamentary majority with perhaps 38% of the national vote (one of the smallest vote shares with which any party has ever won a general election in British history).

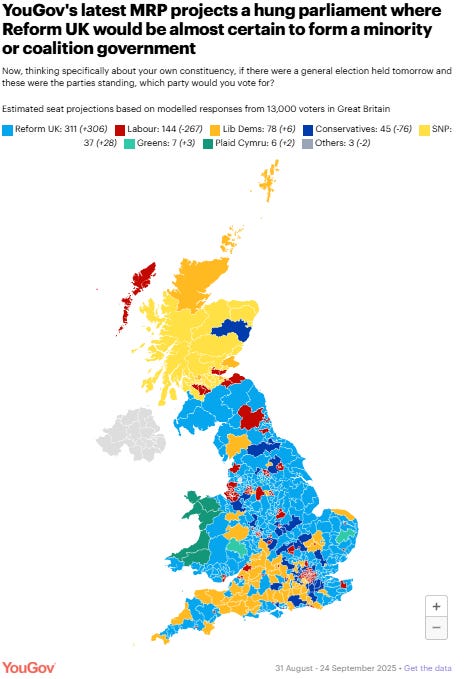

YouGov’s projections show this as plausible.

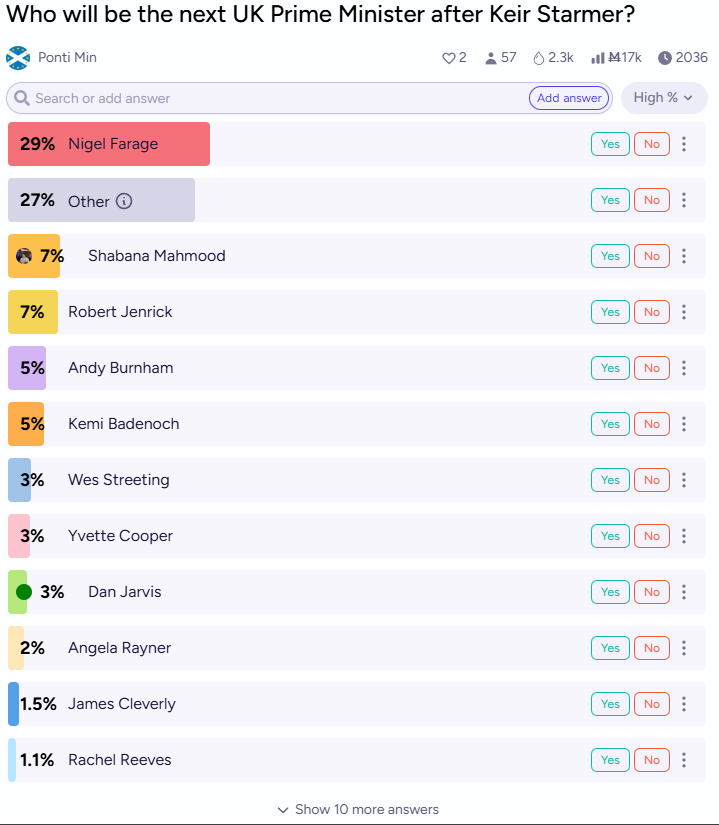

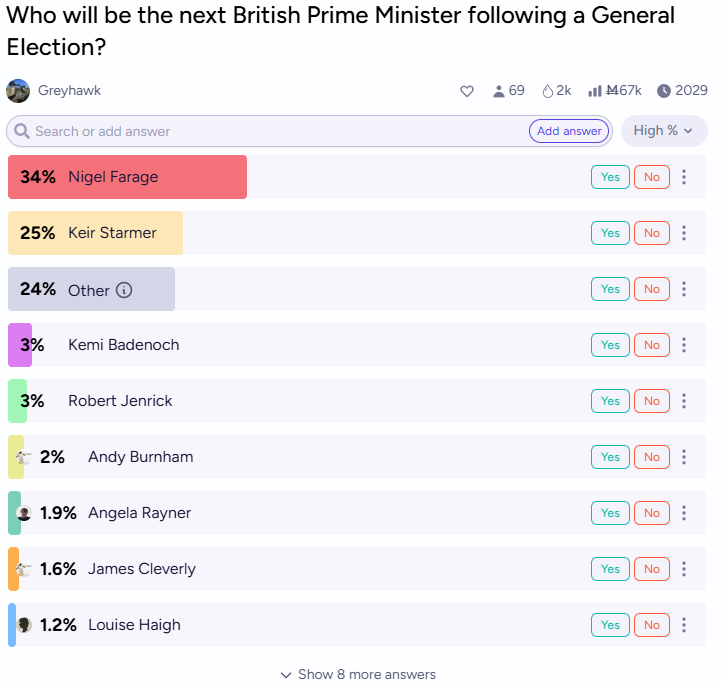

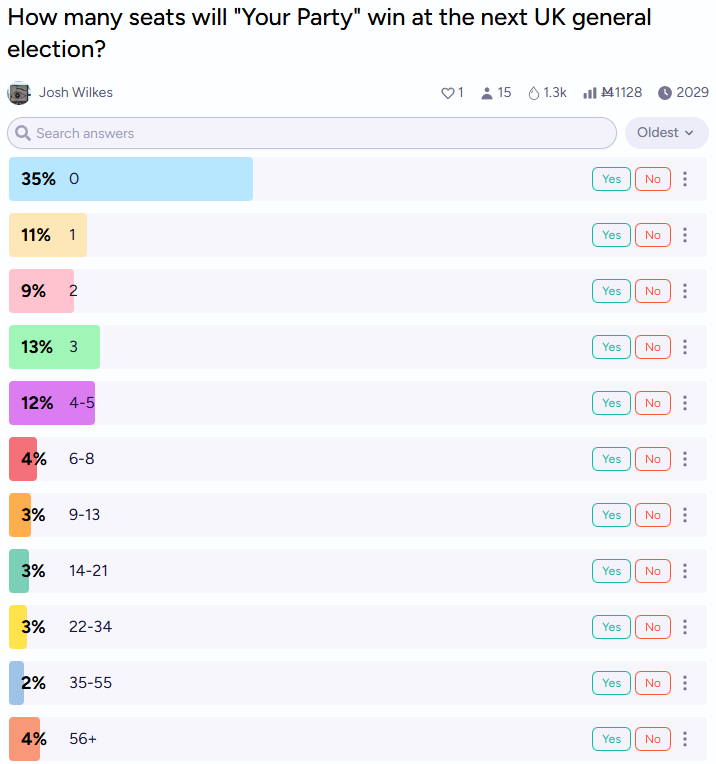

Manifold traders give roughly 30% odds of Farage becoming Prime Minister.

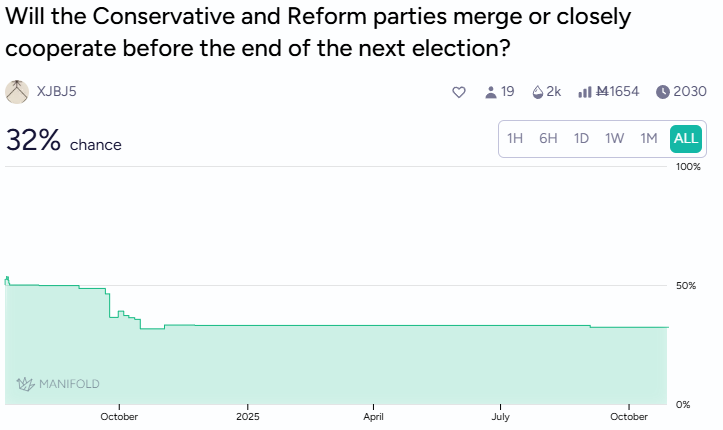

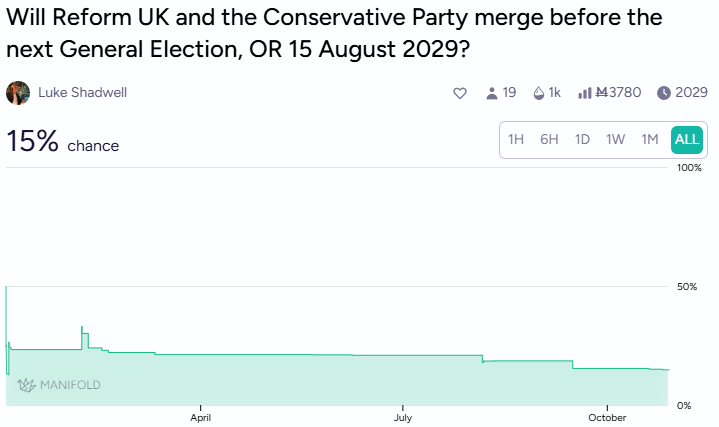

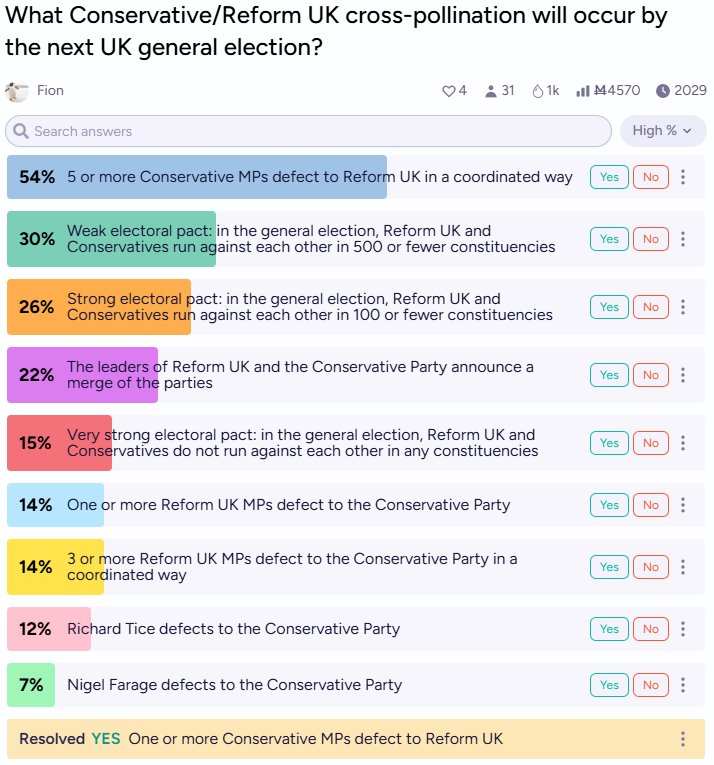

Markets give decent odds of a Reform-Conservative merger, but this misses the point. Farage doesn’t want to merge; he wants to replace.

The question no one seems to be asking is what happens after Reform wins? What will Reform do when they’ve deported the asylum seekers, left the ECHR, and “taken back control,” while Britain still faces anaemic economic growth, NHS waiting lists, and a housing crisis?

The playbook is predictable. First, you blame immigration more intensely to justify a halt to refugee intake. When that doesn’t improve GDP growth, you halt legal immigration entirely. When that doesn’t work, you start reversing recent immigration policy by removing settled status from recent arrivals, thus making Britain sufficiently hostile that people “voluntarily” leave and creating a climate where being foreign becomes a social liability.

And when that doesn’t work either (when the economic fundamentals remain stubbornly resistant to xenophobic policy), you get the kind of escalating extremism where detention without trial becomes “necessary,” human rights protections become “obstacles to sovereignty,” and policies that would have been unthinkable five years ago become the moderate position. You get a ratchet effect where each failure demands more extreme solutions, because admitting the original diagnosis was wrong is psychologically impossible.

This is the trajectory of populist governments that promise simple solutions to complex problems. Britain is about to run this experiment, and the betting markets haven’t quite priced in how destabilising the results might be. What happens when a country gives power to people whose entire political identity is built on the premise that the system is irredeemably corrupt and needs to be torn down? We’re going to find out.

The Perils of Being Boring

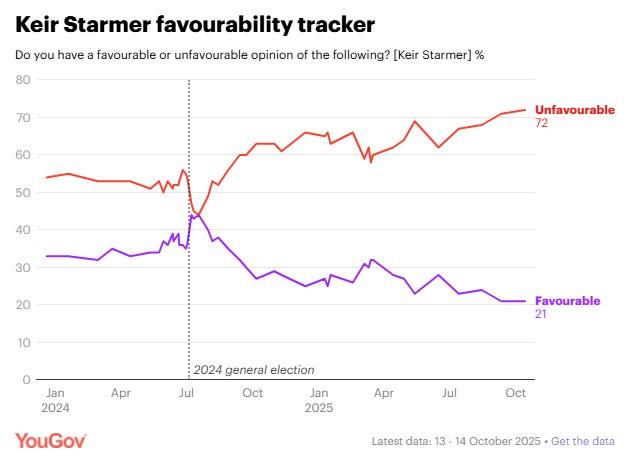

Keir Starmer won a landslide victory in 2024 with all the enthusiasm of a man accepting a prize he’s not entirely sure he wants. Labour’s massive parliamentary majority masks some uncomfortable realities: a vote share that wasn’t particularly impressive, geographic concentration that makes them vulnerable to swings, and a leader whose approval ratings are already trending in directions that should concern his MPs and his Party.

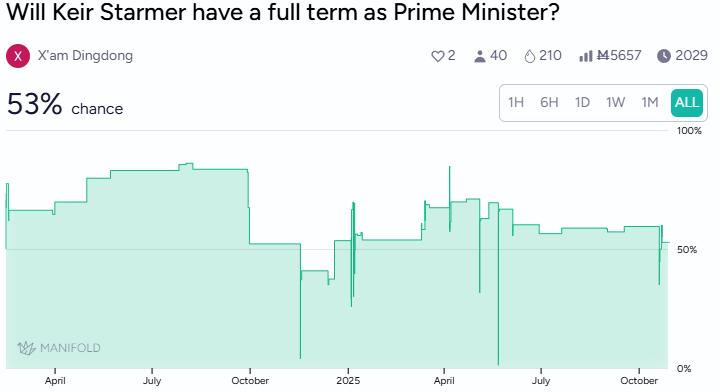

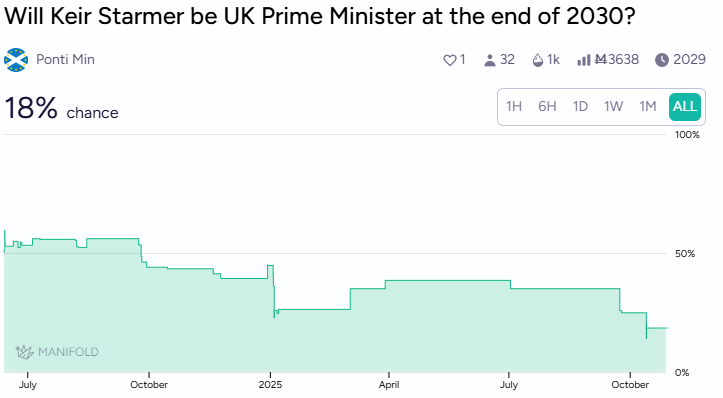

The markets reflect this uncertainty well.

For context, these probabilities are lower than you’d expect for a Prime Minister with a triple-digit majority who just won an election.

Part of this reflects the structural challenges Labour faces. Winning on a platform of “we’re not the Conservatives” works once, but governing requires making actual decisions, and actual decisions alienate actual voters. The farming protests that greeted Labour’s inheritance tax changes offered an early preview of how quickly the coalition that delivered their majority could fracture.

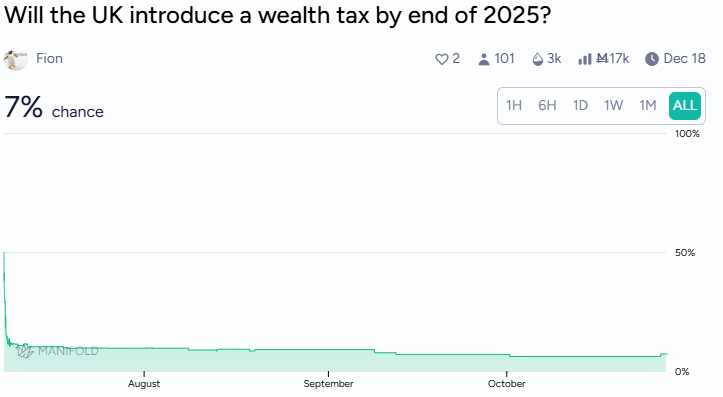

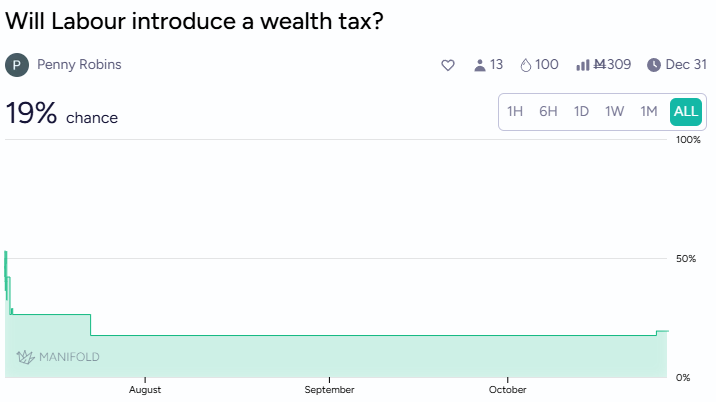

The specific vulnerabilities are becoming clearer by the month. Cost of living continues to squeeze voters while Labour’s policy response on wealth and economic inequality remains conspicuously absent. This creates an opening for criticism from multiple directions as the left attacks them for abandoning redistributive politics, the right attacks them for economic mismanagement, and voters in the middle wonder what exactly they voted for beyond, well, “not the Conservatives.”

Starmer’s political strategy: what one might generously call “Mr Sensible,” sounds appealing if you’re the kind of person who finds beige wallpaper exciting. The problem is that this approach hasn’t worked for anyone in twenty years. It didn’t work for the Tories under May or Sunak, it hasn’t worked for Starmer, and it spectacularly failed to work for Biden and Harris across the Atlantic. Competent managerialism turns out to be a tough sell when people want their problems solved rather than sensibly managed.

The question facing Labour’s next leader (and the markets suggest the real possibility of a new leader before 2029) is which direction to pivot. They have roughly three options, each with its own fatal flaw.

Option one: actually address wealth inequality and economic inequality as central policy priorities. This has the advantage of being genuinely popular and differentiating Labour from Reform in a way that matters. It’s also the option that Labour’s institutional structure and donor base will resist most vigorously.

Option two: double down on sensible centrism, continuing the Blair-era playbook of triangulation and technocratic competence. This has the advantage of feeling safe and the disadvantage of being completely uninspiring. Also, see above regarding its recent track record.

Option three: move hard on immigration, essentially copying Reform’s playbook. This is Labour’s death warrant. Immigration is the issue where Labour will always be fundamentally weaker than Reform. You can’t out-Reform Reform (a fact even Labour is willing to admit): they’re a far-right party and Labour can’t credibly go that far without destroying what’s left of its coalition.

Sovereignty (and other expensive hobbies)

Perhaps no issue better illustrates British politics’ current state than Brexit’s zombie-like refusal to stay buried. In 2016, Leave won. In 2019, Boris Johnson won an election on “Get Brexit Done.” By any reasonable standard, the matter should be settled, at least for a generation.

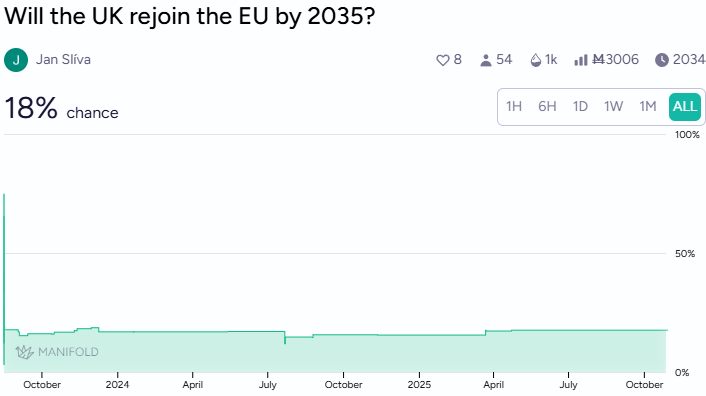

Instead, we have markets pricing in 18% odds that the UK re-joins the EU by 2035.

This might seem low until you remember that five years ago, the odds would have been effectively zero.

The economics of Brexit remain contested: supporters and critics can cherry-pick data to support their preferred narrative, but the political dynamics are shifting. Younger voters overwhelmingly oppose Brexit, demographic replacement is working its slow magic, and the promised benefits have proven elusive enough that “Brexit wasn’t done properly” has become the new defence from its architects.

The Greens’ Unexpected Moment

The Green Party spent most of its existence as Britain’s most intellectually respectable protest vote. That appears to be changing, and changing fast.

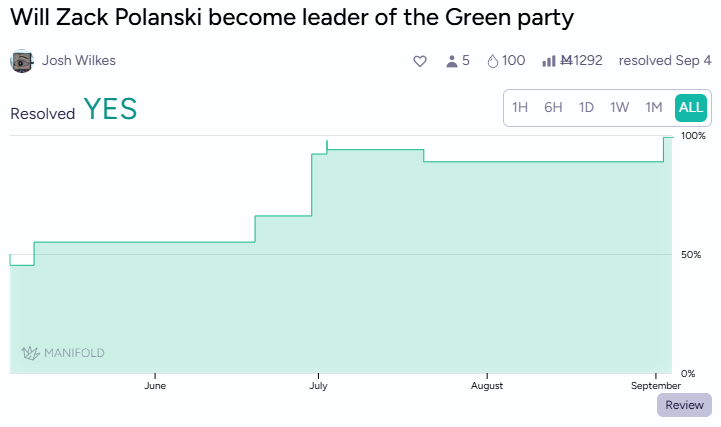

The leadership transition from Carla Denyer and Adrian Ramsay to Zack Polanski in September 2025 marks something more significant than a routine personnel change. It represents a strategic pivot from competent-but-invisible to deliberately provocative, and from parliamentary respectability to what Polanski himself calls “eco-populism.” The results have been remarkable: membership doubled to over 140,000 (surpassing the Conservatives), recent polling shows them neck-and-neck with Labour nationally, and markets say there’s a significant chance that figure may reach 200,000 by the end of 2025.

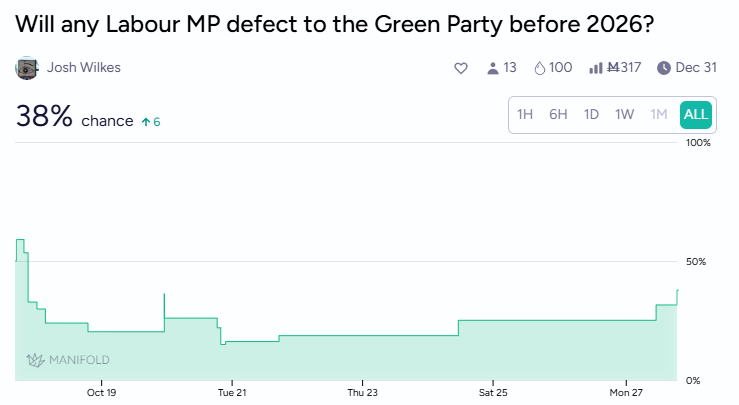

Polanski claims he’s had conversations with Labour MPs in the “double figures” about defecting, with Manifold users saying there’s a 38% chance a Labour MP defects to the Greens before 2025. The spectacle of Labour MPs considering jumping ship less than a year and a half into Starmer’s government would be politically explosive, not because it would threaten Labour’s majority, but because it would signal that the party’s left flank has concluded the project is beyond redemption.

Denyer and Ramsay delivered the Greens’ best-ever election result in 2024: four MPs, 6.7% of the vote, over 850 councillors. By conventional metrics, their leadership was successful. The problem, as identified by everyone from Novara Media to internal party critics, was that nobody knew who they were.

Over half of Green voters in 2024 didn’t recognise Denyer; 86% couldn’t identify Ramsay. When your own supporters can’t pick you out of a lineup, you have a visibility problem.

Enter Polanski, who won the leadership with 85% of the vote by explicitly promising to emulate Reform’s media strategy while channelling the discontent toward wealth inequality instead of immigration.

His media appearances since becoming leader have been unapologetically combative: calling the framing of the migrant crisis “racist and fascist,” arguing that people should worry more about private jets than small boats, telling Labour to stop “aping” Reform, and declaring his intention to “replace” rather than merely cooperate with Starmer’s government.

This is a calculated break from the Green Party convention. The party has historically positioned itself as the sensible environmental alternative through evidence-based policy and technocratic competence, and by being the adults in the room who understand climate science. Polanski is betting that what voters actually want is someone angry on their behalf, someone willing to draw clear lines between the people and the elites, someone who can channel economic frustration into progressive rather than reactionary politics.

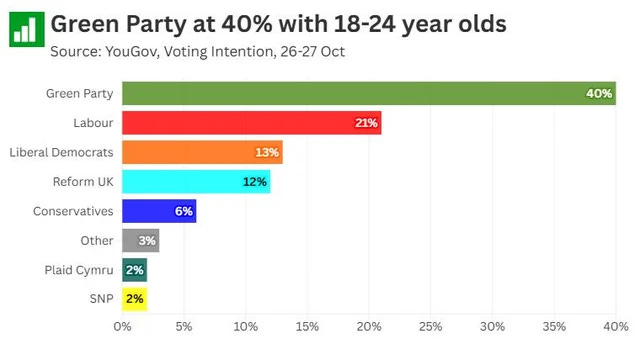

The early evidence suggests he’s right, at least with younger voters.

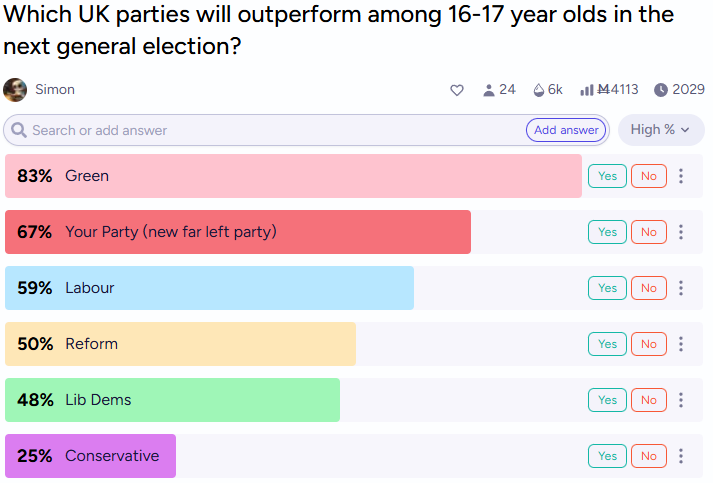

The Greens now poll at 40% among Gen Z voters and lead with all voters under 50. Among 18-24 year olds specifically, support has surged 12 points to 30% while Labour has collapsed 18 points to 23%.

What the Greens will now need to do is mobilise this voting intention to have any actual impact (we have seen far too many precedents of younger voters being big on preferences and low on voting).

Across the Atlantic, Zohran Mamdani’s campaign in New York encouraged younger people to canvass, and because of that, young people got Zohran the nomination (and now, the election). The Greens will probably do something similar (and need to). Polanski has actually mentioned that he and Zohran’s team have been collaborating on communications, and it’s obviously working.

It could be too early to say, but a shot in the dark is that the centrist Labour-Conservative duopoly is dying out and being replaced with a Reform-Green one.

The question is whether “eco-populism” can actually scale. Reform demonstrates that right-wing populism works in Britain; whether left-wing populism can achieve similar results remains to be seen. The Greens are about to find out whether you can borrow Reform’s playbook without borrowing their politics.

The Also-Rans

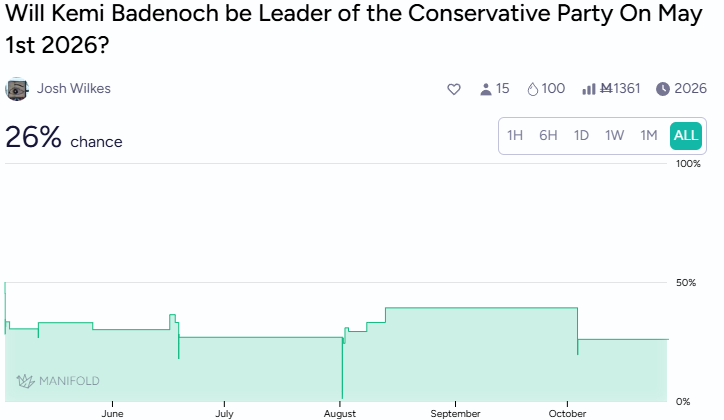

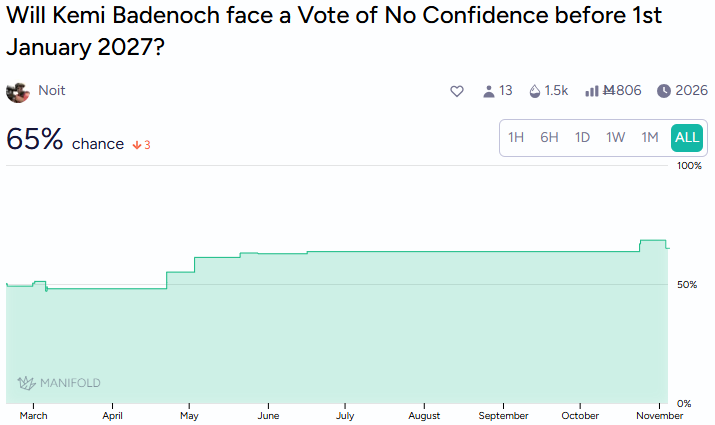

The Conservatives, currently led by Kemi Badenoch, face an interesting strategic proposition: when you’re losing this badly, being crazy is often a good solution. The party will almost certainly see another leadership change before 2029 (stability being a luxury reserved for parties that aren’t facing potential extinction).

The Tories’ path forward likely involves more rather than less craziness, simply because maintaining a sensible centre-right position means competing for the same voters as Liberal Democrats while losing their right flank entirely to Reform.

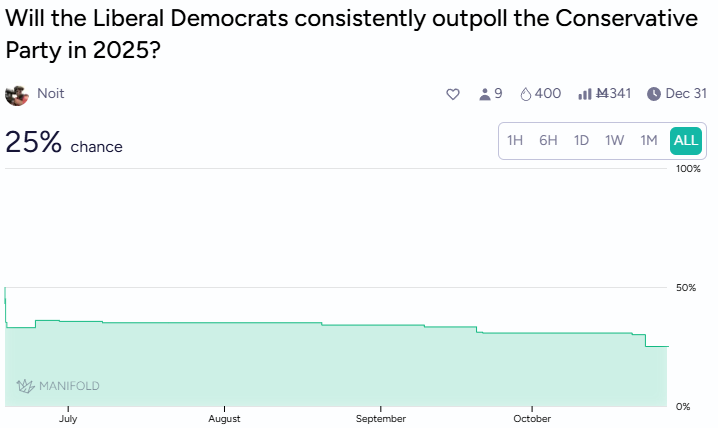

The Liberal Democrats, for their part, had a good 2024 election but remain fundamentally uninteresting. They captured most of the wealthy, educated voters fleeing the Conservative Party (basically, rich people who wanted Brexit to go away and found Reform too vulgar). This is a reliable constituency but not a growing one, and its ceiling remains clear.

Corbyn and Sultana’s new party should theoretically fill the gap on the far left created by Labour’s rightward shift. The problem is they’re doing a spectacularly abhorrent job of it. Rather than focusing on economic inequality or housing or NHS privatisation (issues that might actually resonate with disaffected Labour voters), Sultana seems preoccupied with criticising the Greens over NATO policy and the finer points of whether diplomatically recognising Israel is the right decision after condemning them and recognising Palestinian statehood.

The result is more left division over issues that aren’t particularly bothersome for the general left-wing voter, while Reform consolidates the right with remarkable efficiency. Meanwhile, the party’s leadership appears more concerned with the mechanics of how the party will be structured than offering any strategic insight into whether they’ll be in a solid position for 2029.

The projection that they might win seats in the low single digits needs to be understood in this context: in a fragmented landscape where Labour is haemorrhaging support, even marginal parties can win representation. But representation without influence is just expensive symbolism, and right now that’s the ceiling for a party that seems more interested in ideological purity than political strategy.

The Scottish Question, Again

Scotland never really stopped asking the question; Westminster just stopped answering. The 2014 referendum was supposed to settle the matter for a generation, but that was before Brexit, before COVID, before the SNP’s recent scandals, before the whole edifice of British politics started showing cracks.

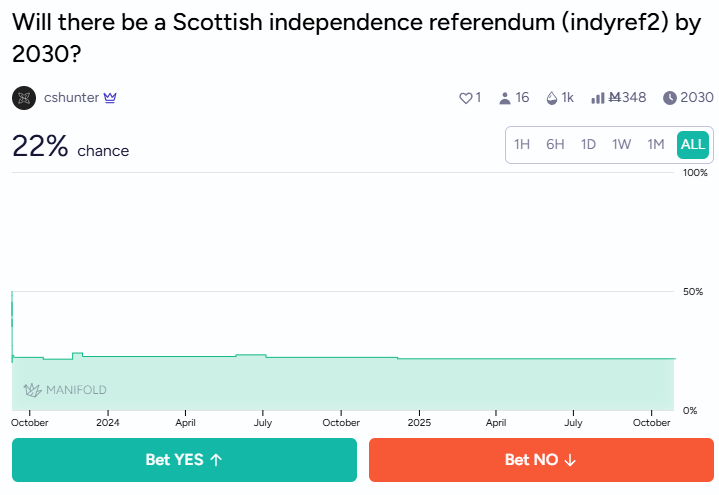

Recent polling suggests support for independence hovering around 50-50, which is either encouraging or terrifying depending on which side you’re on. Markets price in non-trivial odds of another referendum happening this decade, though whether Westminster grants one legally is a separate question from whether Scottish voters would support independence if given the chance.

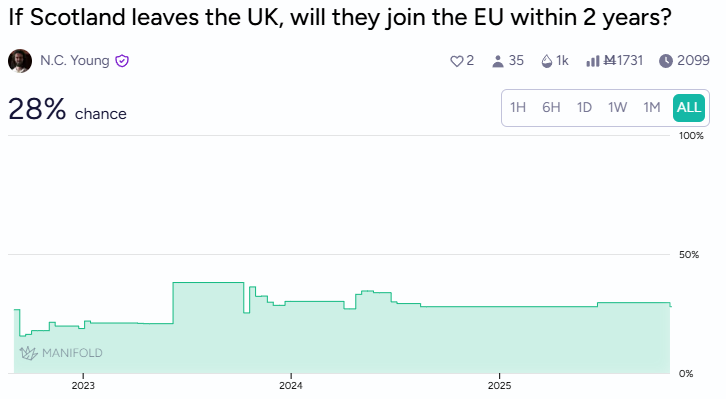

The EU dimension remains crucial. Markets give an independent Scotland a 28% chance of re-joining the EU, creating the bizarre possibility of Scotland in the EU, England out, and a border between them that would make the Northern Ireland Protocol look straightforward by comparison. The customs implications alone would be spectacular.

The SNP has had recent difficulties, including leadership turnover, financial scandals, and a sense that the independence movement has plateaued, all of which have paradoxically made the question more rather than less urgent. If independence doesn’t happen soon, there’s a real risk (from a nationalist perspective) that the moment passes, that younger Scots become less enthusiastic, and that the whole project loses momentum. Hence, there is pressure for another referendum sooner rather than later.

The 2029 Event Horizon

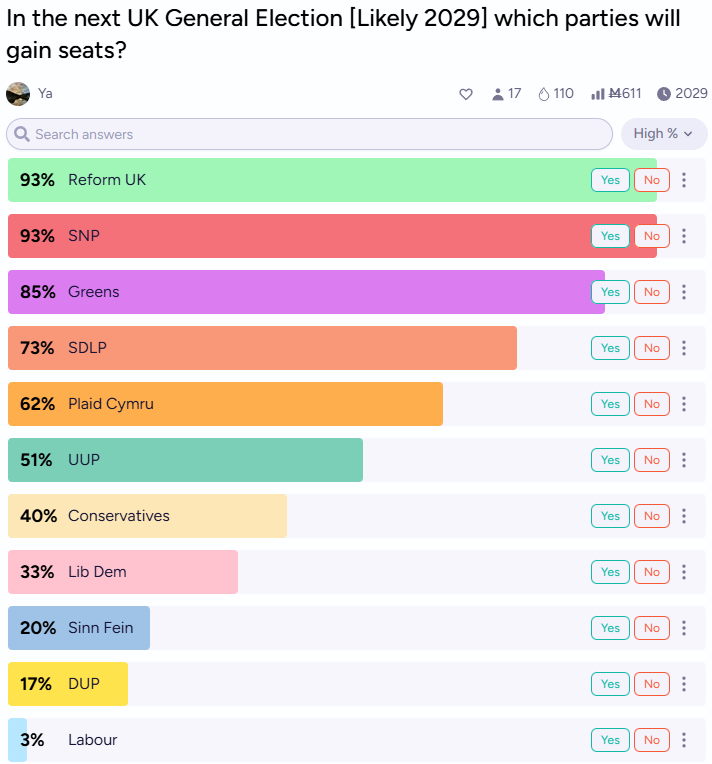

All of this builds toward the 2029 general election, which increasingly looks like it will determine whether the last few years were a temporary spasm or a genuine realignment. Will Reform replace the Conservatives as the main right-wing party? Will Labour hold its majority against attacks from both flanks? Will Scotland still be part of the UK? Will Brexit still be considered irreversible?

British politics has always had a theatrical quality, a sense of performing continuity even as everything changes. That performance is getting harder to maintain, and the markets are noticing.

-Happy Forecasting!

Above the Fold

Uh liberal economic policies in Argentina are quite different from illiberal economic policies proposed by Reform. Grouping these two together as the same is part of the UK's problem.

Wow, great analysis! That was a terrrific read. Cool to see non-American politics.